When Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron announced this year that his office planned to take at least $42 million from state money and use it to fund corporate research for an experimental psychedelic addiction treatment, he caught many people off guard—including some of the officials tasked with allocating that money.

The proposal—to fund development for the alternative therapy ibogaine—and the continuing mystery of Cameron’s decision, immediately became a flashpoint in the state. Democrats and addiction specialists are particularly puzzled why Cameron and his allies are so insistent on studying ibogaine—an obscure, unproven, and possibly “perilous” plant-based treatment that makes you violently ill and whose advocates include military veterans, Melissa Etheridge, Lamar Odom, and the original Wolf of Wall Street.

The $42 million grant is due to come out of the state’s landmark $842 million settlement that Kentucky won last year from opioid manufacturers, after their addictive products precipitated hundreds of thousands of opioid deaths in America.

The state administers its cut of the money through a group called the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, which is housed under Cameron’s AG office. Cameron appointed a majority of the commission’s 11 members, including its chair, state attorney W. Bryan Hubbard. After a series of public and private hearings on the ibogaine project, the commission is set to vote on the proposal next month.

Adding to the mystery is why the members who Cameron appointed to the commission have taken so quickly and stolidly to this specific treatment.

While a number of advocates with no clear Kentucky political connections have invested time and energy in the effort, there are other players with clear financial and political ties—for an experimental psychedelic drug that surprisingly leaped to the front of the line for the commission’s exponentially largest grant yet.

The politics of the issue are unavoidable. Ibogaine didn’t appear to be on the opioid commission’s radar until Cameron and Hubbard announced the grant proposal on May 31—in one of the most conservative states in the country, where Republicans (including Cameron) reluctantly got behind legalized marijuana just this year.

No one on the commission had even discussed the ibogaine idea with members appointed by Cameron’s political opponent, Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear, until Cameron and Hubbard held a press conference proposing the deal in late May.

A person with knowledge of Beshear’s thinking told The Daily Beast that the ibogaine proposal was a shock to the governor and his staff, and it came against the wishes of the stakeholders in the state most familiar with these treatments.

“Cameron came out of the blue with this, and it caught everybody off-guard that’s close to the issue,” this person told The Daily Beast. “And the individuals running recovery facilities are behind the scenes very opposed to taking those funds away from the facilities.”

“It’s blood money, and those funds were intended and committed for those people working every day in the recovery field. There was never any talk of the money being used for corporate R&D,” the source continued. “That money, we understood, was for groups working every day to help people recover.”

But The Daily Beast’s investigation into the people and entities behind this project revealed an intricate nest of political and corporate ties. Those ties include a sitting U.S. Senator, a top GOP strategist, and a billionaire Republican megadonor who recently put millions of dollars into a group backing Cameron’s faltering gubernatorial campaign.

That megadonor, longtime conservative financier Jeff Yass, stands to reap massive profits from the development of ibogaine, which, despite its controversies and health drawbacks, has begun to attract a niche following of devoted patients and investors as a potential miracle cure to break opioid addiction.

Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron delivers a live address to the largely virtual 2020 Republican National Convention.

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

Yass’ firm sharply increased its investment in ibogaine research around the time of Cameron’s announcement, and executives at two of the firms Yass is invested in have rallied openly for the Kentucky program, including in public hearing testimony this summer.

Today, the gubernatorial election and that $42 million research grant are both barreling towards votes this fall. But while the public will get to decide Cameron’s fate—and his hopes have dimmed—the corporate grant still looks poised to sail through. That’s in part because those voters are all on a government commission, and the majority of them were personally appointed by Cameron.

About a week after Cameron’s ibogaine announcement, Yass gave $3 million to a super PAC that has recently pumped out at least $1.2 million worth of ads backing Cameron’s candidacy, according to Federal Election Commission filings. That donation has accounted for roughly 98 percent of the group’s total reported fundraising this year.

And while the commission has already allocated a number of grants, this one stands out.

The OAAC has so far distributed its grant money to grassroots enterprises—local municipal programs, law enforcement organizations, addiction and recovery centers, faith-based groups, frontline workers, and the like. But this grant would be a public-private partnership with a pharmaceutical firm, subsidizing corporate research and development, with the firm matching the $42 million.

Notably, this single grant is also much larger. According to the commission’s website, the panel has so far distributed $32.5 million, scattered across 59 groups—or about $10 million less total than it plans to give to a single ibogaine corporate partner. The largest single allocation to date is $1,000,000. The ibogaine grant would provide $7 million a year for six years.

Perhaps more importantly for the firms, however, the partnership with Kentucky would give them a state where they could conduct clinical trials for a drug that is currently illegal in all 50 states and every country but Mexico and New Zealand.

Those facts—combined with the GOP-led commission’s striking decision not to consult its Democratic members about the proposal ahead of time—immediately rang alarm bells for Democrats, especially for Beshear.

The opioid commission has never clarified the origins of the proposal. Its chair, the Cameron-appointed Bryan Hubbard, has claimed sole credit. But the political and corporate connections are difficult to ignore.

The Daily Beast sent detailed comment requests to Cameron’s campaign and office, as well as to Hubbard.

Hubbard, who works in the office of attorney general, declined to answer questions on the record. After an off-the-record phone call, Hubbard texted The Daily Beast the email address of Brett Waters, the head of a nonprofit that has been closely involved in the ibogaine project from the beginning.

Waters is co-founder and executive director of Reason for Hope, a group whose CEO—a former Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) appointee—joined Hubbard and Cameron at the May 31 press conference.

Days earlier, Reason For Hope had retained the lobbying firm run by former Sen. Tom Daschle (D-SD) to advocate on the federal level for the Breakthrough Therapies Act, Politico reported.

Reason for Hope is, as Waters told The Daily Beast, deeply committed to advancing the safe and effective development of alternative therapies to help untold millions of Americans struggling with trauma and addiction. The group has no corporate backers, Waters said. He also called Hubbard an “incredibly positive figure” in this process, one who ensured that “diverse voices” contributed to the discussion, including indigenous voices. (The commission features one non-white member—a Cameron appointee—and has been called out for lack of diversity; Cameron, meanwhile, has attacked workplace diversity initiatives throughout his campaign.)

“He is genuine in his desire to help people break free of substance use disorder, and this is a brave proposal,” Waters said of Hubbard.

A spokesperson for the AG’s office provided a 264-word statement expressing confidence in the commission and promoting the Kentucky Opioid Symposium, which takes place Monday and Tuesday. While the statement touted the $32.5 million in previously allocated grants, it did not address almost any of the detailed information and questions we provided as the focus of this article. The office did not respond when offered the chance to follow up.

However, the statement said the “planning and co-hosting” for this conference “required that certain agenda items be pushed until the Commission’s November meeting,” apparently in response to the question of why the vote on the grant was pushed back to Nov. 15—a week after the election, and more than a month after the symposium. (The Daily Beast has since learned that opposition researchers in recent weeks have requested records from Cameron’s office related to the ibogaine program.)

The statement also noted that Hubbard had “invited every member of the Commission” to the May 31 press event. The criticism from the members, however, was not that they hadn’t been invited to a press conference, but that they had not discussed the proposal at all before Cameron made his “fait accompli” announcement, as one Democratic member of the commission described it.

Yass—the fourth-largest megadonor in the country and the wealthiest person in the state of Pennsylvania with a net worth estimated over $25 billion—stands to profit massively from ibogaine, especially in the long run.

Yass’ investment firm, Susquehanna International Group (SIG), currently holds around $5 million in ground-floor stakes with four biopharmaceutical firms focused on developing psychedelic addiction treatments. More than $4 million of it lies with two entities leading the charge on ibogaine, according to SIG’s August filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

While it may be natural to downplay those numbers in the context of SIG’s sprawling $491 billion portfolio, those pharmaceutical companies are currently trading low. If treatments like ibogaine gain traction with the public—and more importantly, with regulators—that niche market, and those holdings, will explode. As The Daily Beast previously reported, the entire purpose of the Kentucky program is to help ibogaine receive federal approval as a “breakthrough therapy,” which would “accelerate the regulatory pathway for legal status nationwide.”

As it turns out, the Kentucky opioid commission has tapped Yass-backed corporate entities to help make the case for ibogaine investment.

In July, the commission held a public hearing where health experts and scientists touted the benefits of ibogaine. Two of those scientists, however, were also engaged in a joint corporate venture involving ibogaine.

And yet, the meeting agenda published by the OAAC only discloses the corporate background of one of them—Dr. Srinivas Rao, co-founder of German biopharmaceutical firm ATAI Life Sciences. The other person in the joint venture, Dr. Deborah Mash, was only identified as professor emerita at the University of Miami School of Medicine, not in her capacity as founder and CEO of DemeRx—where ATAI holds majority control, according to SEC filings.

Yass has stakes in ATAI, which is heavily backed by another billionaire Republican megadonor, Peter Thiel. DemeRx is an ATAI subsidiary, and ATAI also owns a considerable share of another one of Yass’ psychedelic investments, Compass Pathways.

According to an SEC quarterly filing submitted in August, after ditching the stock entirely months earlier, Yass’ firm upped its ATAI investment significantly between April 1 and June 30. That filing also shows about $3.6 million in a company called Mind Medicine, which has been conducting ibogaine opioid abatement trials. All of these investments would stand to give SIG exponential returns if regulatory gatekeepers begin to clear the way for ibogaine development—and a partnership with a state government is a major step along that path.

But it’s not just Yass. The opioid commission and its work on the issue so far bears a number of ties to a man named Rex Elsass, an influential longtime GOP strategist and media buyer who has performed millions of dollars of work for Yass-aligned groups.

Elsass’ son, Reid, died tragically of an overdose, and his family created a nonprofit called the REID Foundation dedicated to recovery efforts, including emergent therapies. Last month, Elsass, an Ohio resident, spoke movingly at a public hearing in support of ibogaine, reportedly describing himself to the commissioners as “your neighbor next door” without apparently disclosing his long and unavoidably political background.

A partner organization of Elsass’ nonprofit, called Reason for Hope, also provided officially sanctioned testimony in the same hearing, and their CEO—a former Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) appointee—took part in the May announcement.

Days ahead of that announcement, Reason for Hope brought on a top federal lobbyist—Daschle—to advocate for the Breakthrough Therapies Act. The nonprofit’s CEO—retired Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Martin Steele—had been previously appointed to a federal veterans’ health care commission by Cameron’s political mentor, McConnell.

Additionally, a former adviser at Elsass’ company, The Strategy Group, named Sally Hauser, now heads a group called the Kentucky Ibogaine Initiative, according to her LinkedIn. The nonprofit just registered with Kentucky this year. (Hauser’s position with the group disappeared from her LinkedIn page at some point after The Daily Beast sent out comment requests.)

Elsass told The Daily Beast in a phone call that, to the best of his knowledge, he had never met Jeff in person, and that he had been first tipped to Kentucky’s potential by the Etheridge Foundation, started by folk-rock LGBTQ icon Melissa Etheridge. He explained that his ibogaine advocacy—a “miracle medicine that needs to be researched”—is rooted in deep, personal loss and a desire to help mitigate tremendous future tragedy.

“The solutions just weren’t there, and I was desperate for new methods to help my son. So we looked for other means, and as a result, he ended up in Peru,” he said, referencing where his son received his first iboga treatment. “Plant medicines helped him and extended his life for several years, and left me with a mission.”

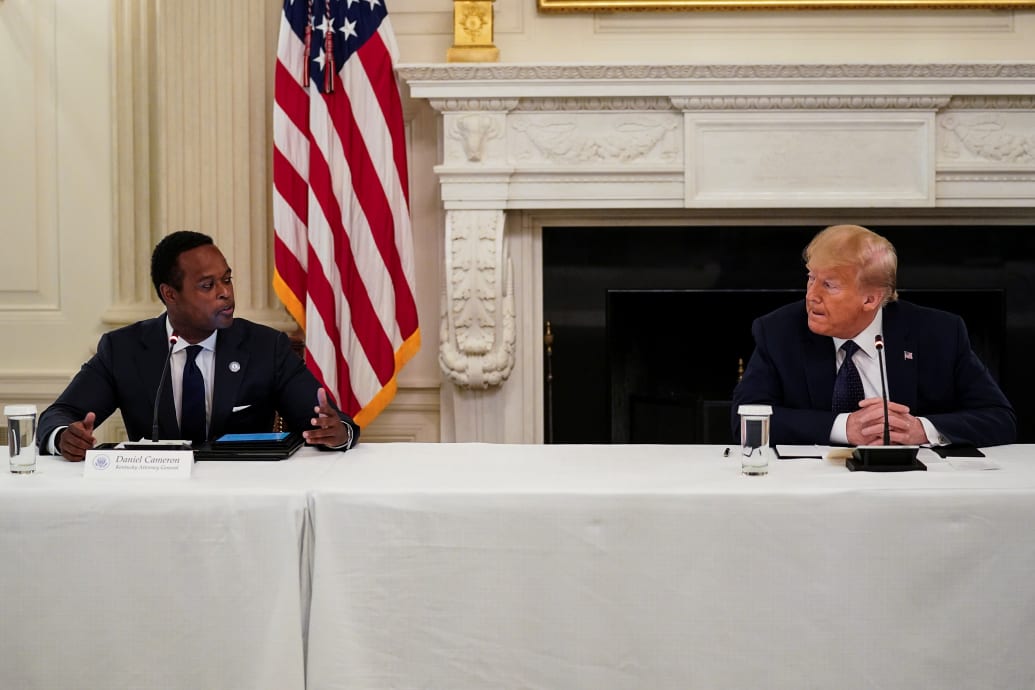

President Donald Trump listens to Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron during a roundtable discussion with law enforcement.

Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

Ibogaine, which is derived from the iboga plant, found in West Africa, has shown anecdotal promise for curbing opioid use disorder—a notoriously difficult medical problem that often frustrates and frequently appears to defy treatment. However, ibogaine’s U.S. clinical trials have been marred by the drug’s tendency to cause heart attacks. Today, ibogaine is illegal in almost every country, including the United States, where it’s classified as a Schedule I substance—the same level as heroin, cocaine, and LSD—meaning it has no accepted medical benefits and carries a high risk of abuse.

Ibogaine, like cannabis, psilocybin, and MDMA, has begun to attract attention as an alternative therapy, but with the caveat of what TIME magazine described as “perilous” health risks. The drug, like other psychedelic treatments, is said to help patients contend with trauma, which many addiction and behavioral scientists believe to be at the root of a large portion of drug addiction and abuse cases. (Some military veterans credit ibogaine with managing their PTSD, and a few testified to that effect this summer in Kentucky.)

Along with that attention, of course, comes a lot of money. But most institutional research shut down years ago, after clinical trials delineated a clear correlated increase in risk in cardiac events. There isn’t a wide body of sanctioned research on the drug, and many of the recent studies have drawn from small sample sizes.

While the medical, social, and financial benefits from a miracle drug to combat opioid use—which claims about 100,000 American lives a year—might be immense, they won’t certainly won’t be immediate. Even with a massive funding push and a smooth run of trials, Food and Drug Administration approval might still be 10 years away, according to the CEO of ATAI Life Sciences.

Of course, the Kentucky proposal is designed to help with that. Kentcuky would become the first state in the country to legalize ibogaine trials, a major and necessary step on a path towards deregulation. As Hubbard said in May, a key component is to “incubate, support and drive the development of ibogaine all the way through the FDA approval process.”

He added that Kentucky would also work to create “the platinum standard model” for ibogaine recovery treatment, which the state would do “by hosting multi-site clinical trials right here at home.”

Still, the drug has a committed base of support. Advocates include military veterans, addiction survivors and families, and political players like former Texas Republican Gov. Rick Perry. Last year, Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) teamed up with conservative Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) to introduce a bill that would make it easier for patients to access controlled substances for medical treatment, starting with psilocybin and MDMA. (That news caught the eyes of investors in the small but burgeoning psychedelic stock trend—as did Cameron’s Kentucky plan.)

Paul, it turns out, also goes way back with Yass.

Last October, the Louisville Courier-Journal said Paul was Yass’ “favorite politician on the national scene.” The relationship also runs deep, with Yass pouring more than $15 million into the Paul-aligned “Protecting Freedom” super PAC since 2017, according to Federal Election Commission data. Protecting Freedom also contracts with Elsass, with one of his entities as its top vendor in the 2022 cycle, according to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics.

It also turns out that Yass made his largest-ever contribution to that very same super PAC—a flat $3 million—on June 8, about one week after Cameron’s ibogaine announcement. Then, in August, as Cameron’s polls dropped, the super PAC put that money toward a series of political ads supporting Cameron’s campaign and attacking Beshear. Another Yass-funded super PAC, called “School Freedom Fund,” also began pumping out ads around the same time, the Kentucky Lantern reported.

Paul is another late-comer to the pro-Cameron camp. He didn’t make an endorsement in the primary, but after the Protect Freedom ads went up, Paul began speaking up for the AG—and appearing at events with him.

But even without the political intrigue, which has not yet been reported, Cameron’s announcement raised a number of eyebrows. That’s in part because he hadn’t consulted members of his own commission in advance, but also because it was difficult for some Kentuckians to understand why, with so many urgent needs in the addiction and treatment communities, Cameron seemed so intent on funding research into this singular alternative therapy—which likely won’t even be authorized for medical use within a decade, according to the commission’s own expert testimony. (Again, Cameron only embraced legalizing marijuana in March, after years of hedging on the issue.)

In 2022, Cameron’s office won a long-fought court battle against opioid manufacturers, carrying on the work of his AG predecessor and now political rival Gov. Beshear. The legislature then tasked Cameron with managing the fruits of that victory, an $842 million settlement paid out by opioid manufacturers whose products have ravaged the state for decades.

Half of that $842 million went directly to Kentucky cities and counties, with the oversight and allocation of the state’s remaining half falling to the advisory commission. The $42 million in the research grant, Hubbard has claimed, would correlate to the same amount the legislature recently allocated to an alternative release program that reroutes qualifying criminal offenders with mental health and substance use issues to community support programs, covering 11 counties. (The offices of Kentucky’s governor and attorney general are both the subject of a Justice Department investigation into whether the state “subjects adults with serious mental illness” in the Louisville area to “unnecessary institutionalization,” as opposed to community programs; Louisville is in one of the counties that won’t receive benefits from the alternative release bill.)

While the OAAC is a bipartisan group, the legislature empowered Cameron to pick the chair of the 11-member commission, along with five other members, giving Cameron majority control.

After Cameron’s surprise announcement in May, Beshear’s two political appointees on the commission pushed back immediately, questioning the opacity of the proposal’s origins and expressing skepticism about subsidizing a corporate partner on what appears to be a narrowly-tailored moonshot.

The lone academic representative, Dr. Sharon Walsh of the University of Kentucky, also pushed back in a June preliminary hearing—and put her finger squarely on what she said was “a clear conflict of interest.”

Walsh asked Hubbard—a state attorney—why the focus on ibogaine specifically, as opposed to other proven treatments.

“I’m not sure why we need other drugs to target opiate withdrawal,” Walsh said. Hubbard replied that “there are others” who argue it’s a worthwhile option.

Walsh then singled out Mash, the DemeRx CEO.

“So she’s going to come and talk to us about the development of this with it, you know, with the hope of getting money. There’s a clear conflict of interest from a person who has ownership of a company whose sole purpose is to get the drug to market,” Walsh said. “That’s why I’m asking for balance.”

Walsh resigned from the commission this month, and her name is no longer on the website. Two people familiar with the events told The Daily Beast that she stepped down in protest of funding ibogaine, which does not have FDA approval. (The AG’s statement to The Daily Beast thanked her for serving on the Commission, and said that “she and her tremendous expertise will be missed.”)

While these connections have not been previously reported, the ibogaine proposal was so out of the ordinary that it almost immediately raised questions of potential pay-to-play.

In June, longtime Lexington Herald-Leader columnist Linda Blackford raised the specter of political influence.

“To make such a splash over one civil servant’s research into one drug looks strange, especially when that civil servant’s boss is running for governor,” Blackford wrote, referencing commission chairman Hubbard’s impassioned support for ibogaine. Blackford also searched Kentucky and federal filings for evidence that Mash, the DemeRX CEO who testified at the first public hearing, had contributed to groups supporting Cameron.

Blackford didn’t find any donations, and The Daily Beast’s review of campaign finance filings shows Mash is, if anything, a committed Democratic donor. Even so, Blackford wasn’t convinced.

“If you have better information, let me know,” she wrote in her column.

The ibogaine controversy comes after reporting of financial conflicts of interest between Cameron and political donors with business before his AG’s office. While the Yass-funded super PAC entered the fray as Cameron was absorbing major losses to Beshear in both polls and fundraising, the air support hasn’t been able to reverse that negative trend.

And while the commission will decide the fate of the ibogaine funding on Nov. 15, Kentucky will have already elected its next governor.