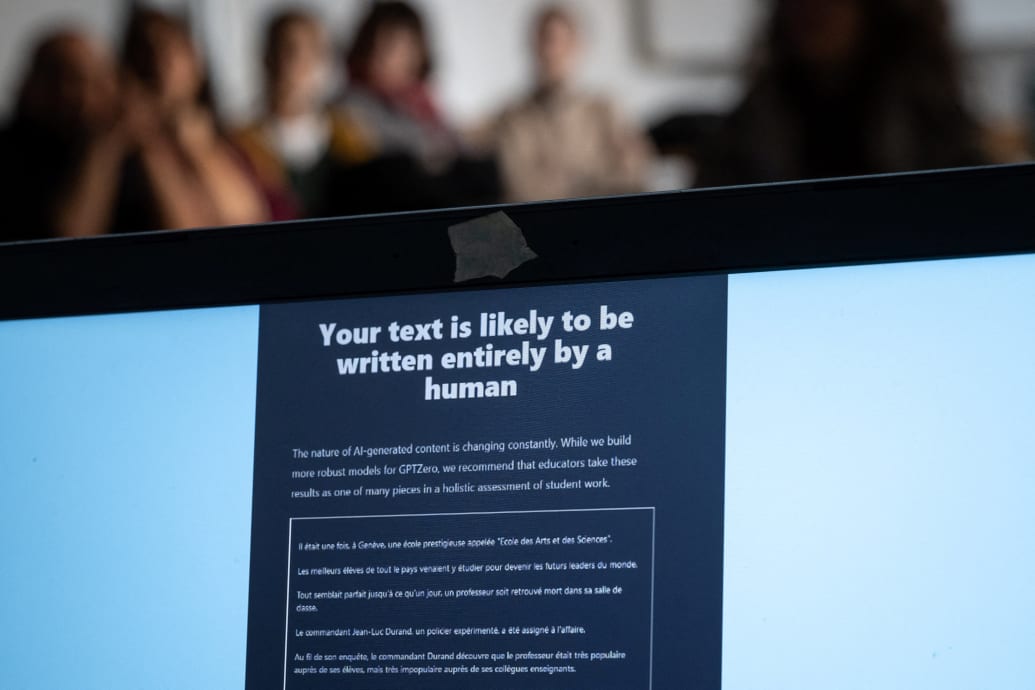

Mira is a student of international business at the Artevelde University of Applied Sciences in Belgium. She recently received feedback on one of her papers—and was shocked to see that her instructor noted that an found that AI detectors have an obvious “bias” against the latter category. Shane further points out that, there have been observations that there is a similar “bias” shown against work by neurodivergent writers.

Rua M. Williams, an associate professor of UX design at Purdue University, recently shared that someone replied to their email assuming AI had written that message. Williams got back to them pointing out that the text probably seemed that way as Williams is autistic.

“I do think that there is currently an AI panic amongst people, especially instructors, that makes them more suspicious of the authenticity of the words they are reading,” Williams told The Daily Beast. “They are thus more likely to deploy that suspicion against people who naturally use language a bit differently, such as neurodivergent people and English-as-second-language people.”

Alain Goudey, associate dean for digital at NEOMA Business School, also points out that non-native English language speakers often find their work falsely flagged because AI detector’s algorithms work by evaluating a text’s “perplexity.”

“Common English words lower the perplexity score, making a text likely to be flagged as AI-generated,” Goudey told The Daily Beast. “Conversely, complex or fancier words lead to a higher perplexity score, classifying a text as human-written.”

He added that since non-native English speakers use straightforward words, this can lead to their work being flagged as AI-generated. For non-native English speakers, who are already doing the extra work of learning a language, this additional burden can be exhausting and puts them at a further disadvantage.

This is something that T. Wade Langer Jr., a humanities professor at University of Alabama Honors College, has recognized with his own students. He told The Daily Beast that he uses the tools as a starting point for conversations with his students for their side of the story, instead of immediately believing the detectors. He doesn’t rule them out entirely, mostly because of how prevalent and popular AI generators have become. However, he said that “our policy is a conversation, not failure.”

“Anytime a question of academic misconduct is addressed, there is some strain on mental health,” he said. “This is why educators and administrators must proceed with curiosity rather than judgment, inviting a conversation to understand and discern the truth of one’s academic integrity, rather than pass an outright judgment.”

At OpenAI’s developer conference in 2023, the company’s former and current CEO Sam Altman announced that they’d be creating new tools that would allow for greater customization of ChatGPT—making it easier for students to utilize the chatbot to assist with homework.

Getty Images

Without a proper understanding of the consequences, researchers like Sadasivan worry that the long term impact of these would be that it stifles creativity and perpetuates further biases. But instead of these being reasons to ban or remove this technology, though, experts are pushing to re-evaluate just how exactly it can be used.

AI is progressing at a speed that educational institutions seem unable to catch up with. This has led to a reliance on short term solutions like AI detectors, but now that its consequences are coming to light, critics are quick to point out the dangers of relying on them. As technology progresses beyond the pace of traditional education, teachers will need to keep up—and this potentially comes at the expense of students. That’s why experts are pushing for a change in the way both AI generators and detectors are currently perceived, and making sure they aren’t used in a way that causes harm.

“Like any other resource educators use, I think the biggest concern would be to use the resource as a litmus test or definitive standard to judge a student,” Langer said. “It takes more time and effort to have a conversation versus rendering a grade [or] verdict. But instructional integrity demands due diligence, just as much as academic integrity does.”