TOKYO—On July 1, 2000, Lucie Blackman, a former British Airways flight attendant then working as a hostess in Tokyo, went on a date with a customer “near the beach.” Blonde, personable, and quick-witted, she was well-liked by her friends, customers, and co-workers. Hostess clubs were benign places where girls flirted with mostly Japanese customers, poured drinks, and made small talk. Lucie described the job as being a flight attendant but without a plane. The occasional date with a customer outside of the club, a dohan, was part of the work. Her customer had promised her a cellphone—still an expensive and hard-to-obtain item for a Japanese office worker in 2000, even more so for a foreign woman. She assured her friend Louise Phillips that she’d be back by the evening.

She never came home. It was like she had vanished off the face of the Earth. A few days later her family became worried. At first the Tokyo Police thought she might have just been another foreigner who failed to check in with her loved ones—“There were a lot of foreigners working illegally back then. They were often reported missing,” says former Assistant Inspector Masahiko Soejima, one of the detectives who worked her case, in the Netflix documentary Missing: The Lucie Blackman Case, which drops on Thursday.

It didn’t take them long to realize that something was seriously wrong when they learned that a strange man had called Louise and told her that Lucie had joined a cult and would never be back.

Assistant Inspector Soejima told The Daily Beast: “The deeper we dug, the more it became very clear that this wasn’t just a missing persons case. It was something much more insidious.”

“I felt as though she were calling to us to come find her.”

— Captain Satoru Yamashiro

By the time Lucie’s family, especially her boisterous and very concerned father, Tim Blackman, arrived in Tokyo, everyone in Japan, England, and the world was asking: “What happened to Lucie Blackman?”

Full disclosure: One of your reporters, Jake Adelstein, was among the throngs of journalists asking that question. I was working as a reporter for the national news department of the Yomiuri Shimbun at the time and assigned to cover the story—as a gaijin (foreigner) it made sense to have one gaijin investigate what happened to the other. This is why I was interviewed for the documentary—and can be seen in the film guiding and speaking with Lucie’s father and her sister Sophie.

The Lucie Blackman case fascinated the world for a year and was the subject of a critically praised non-fiction narrative, People Who Eat Darkness by Richard Lloyd Parry. Yet, the full-story of the investigation has never been told from the perspective of the detectives who broke the case. While Parry’s book stands firmly on the side of the family, many never understood why the Tokyo Metro Police seemed reluctant to investigate and even to be holding something back from the public.

Rebel Cops

The documentary reveals a bizarre split within the homicide division. It shows how one squad working the case was forced to go renegade and conduct their own out-of-hours investigation into how Lucie vanished. The Japanese version of the doc covers this in even greater detail than the international version.

The documentary sheds light on why the police department seemed disinterested in the case or evasive to the Western media and the family. They believed that Lucie could still be alive and that revealing too much might scare the abductor into killing her. They also feared that sharing information with Tim might result in a leak that would undermine any confession they could obtain down the road. The Japanese criminal justice system puts great weight on confessions with information that only the criminal could have known—himitsu no bakuro is the legal term.

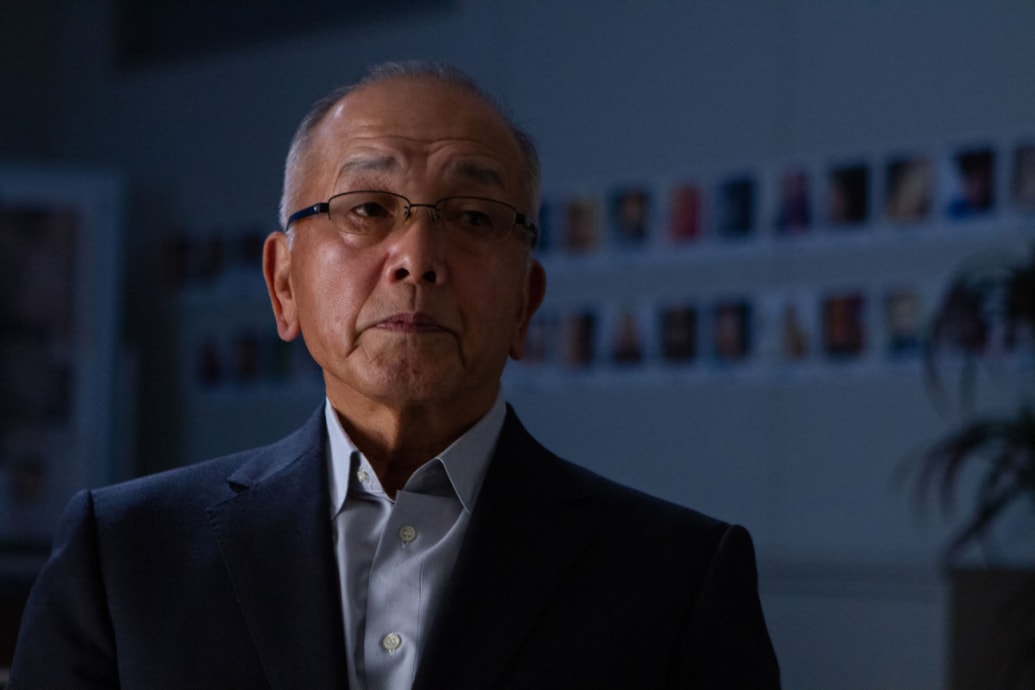

When there’s a major murder or missing persons investigation in Japan, the work is often divided between different squads within the homicide and violent crimes division. In the Blackman case, the Teramae Group, the lead team, had already decided that one of Lucie’s regular customers must be the culprit. The auxiliary squad led by Captain Satoru Yamashiro was supposed to shore up the Teramae Group case, to find the evidence that matched the conclusion.

Yamashiro told The Daily Beast, “We felt that their investigation was missing something.”

The big problem was that Yamashiro and his squad of detectives—known for their tenacity as the “snapping turtle squad”—were convinced the team giving them orders had picked the wrong man, that they were following a red herring. This included Sergeant Junichiro Kuku, who was known for being tough and outspoken. “Once he sinks his teeth into something, he never lets go,” his boss Yamashiro recounted to The Daily Beast. Even in his younger days, Kuku had a face like a bulldog and his deep, gruff recounting of the events and his expressed impatience with the Tokyo Metropolitan Police bureaucracy is a breath of fresh air.

The documentary is also highly unusual for Japan where police officers almost never go on the record discussing a case. And indeed, a police officer who is on active duty can be arrested and jailed for making information pertaining to a case public. Which is why Japanese newspaper articles are full of euphemisms like “sources close to the investigation.” The director Yamamoto also notes that the filming was in a legal gray zone, tacitly acknowledged by the Metro Police but not officially condoned.

It helps that the documentary is based on the non-fiction masterpiece, The Elegy of The Detectives by Shoji Takao, which documented the case in clinical detail.

The movie also shows how the detectives struggle to deal with Tim Blackman. Blackman raises a ruckus believing that the public attention will encourage people to come forward with information that will help the police find his daughter.

He refuses to sit back and watch because he is frustrated with the lack of progress on the investigation.

And it turns out, so is the Yamashiro squad.

And so, as the documentary shows us, members of the squad began sneaking into the offices after hours to work their own leads, Sometimes even camping out at the police headquarters.

The detectives follow every lead “investigating as diligently as crushing lice”—one by one. It was detective Kuku that found buried in the files a report that refocused the investigation.

A young beat cop had talked to a club owner who said that one of his hostesses had gone on a paid date with a customer. He’d taken her up to his resort apartment near the ocean, drugged her, possibly raped her, and then driven her home.

Kuku told The Daily Beast, “I got a shiver when I read that report. And it had been disregarded because the informant was a low-life and a drug addict. But that had nothing to do with the veracity of the information he had to give. And so we followed up.”

They knew something similar had happened to Lucie; she met a customer who was supposed to drive her to the seaside—and then she vanished.

They discovered that this had been happening for years. Maybe over a decade. There was a man with a number of sports cars who had been preying on hostesses—Japanese and foreign—with the same MO. Could this be the guy who had abducted or killed Lucie? The detectives began looking for him in earnest. But that wasn’t their assigned task—so like a team of ninjas, they continued to work the case in the shadows. “We snuck into the offices like thieves in the night,” Kuku reflects.

The detectives, especially the two female police officers on the case, pounded the pavement and found victims who were willing to speak. One of the women had the phone number of the man who assaulted her written in her notebook. The problem? She had left the notebook back home in Australia.

She had her father send it and when they searched the notebook, the phone number was crossed out. They held it up to the light and were able to eke out the number with some degree of accuracy. The last four numbers were very clear. 3301. They were able to figure out the rest of the hazy digits by the process of elimination. And upon checking phone records, they found the number was still active. And not only that—the phone had been used to call a number connected to Lucie Blackman.

But it was 2000. Number-tracing technology in Japan wasn’t like it is in the movies. They could only locate the phone’s real owner by checking where and when it had accessed phone transmission towers. After cross-country travel they triangulated the calls to a business office and residential space in the high-end Moto Akasaka district of Tokyo.

The phone number was a huge leap for the investigation but the fact that the Yamashiro squad had requested the official phone records caught the attention of the top brass. They were not pleased to discover that Yamashiro, Kuku, and company had gone cowboy on them. But no one could argue with their results. Although they were temporarily treated like outcasts in their division, they were allowed to continue their line of investigation and earned the respect of their colleagues.

The documentary follows the detectives as they put the puzzle together piece by piece finally narrowing it down to one clear suspect, a wealthy real-estate owner and businessman with a fleet of luxury cars and a home near the exclusive Zushi Marina. Also a man who avoided having his picture taken to such a degree that it bordered on obsession. He matched up with all the evidence they had found so far. His name was Joji Obara and he had a criminal record. Victims who were shown a large number of mugshots with his photo in the mix named him as their assailant. He was almost certainly their man.

When they finally arrested him on charges of sexual assault, they discovered hundreds of videotapes that Obara had kept of his sexual assault victims, who numbered over a hundred. (Obara was eventually only prosecuted and found guilty of eight rapes and one charge of “rape leading to death” for Australian Carita Ridgeway). He had taped himself assaulting his catatonic victims, using a number of drugs, sometimes using a hook on the ceiling to manipulate them like puppets. In the videos, he was often using a mysterious brown bottle of liquid on a table near where his victims slept.

What was in that brown bottle? It turned out to be an important clue that a forensic pathologist used to connect Obara to a cold case from 1992: the mysterious death of Ridgway, an Australian hostess. The bottle contained chloroform—the same substance that was found in a liver sample from the victim—a sample that the hospital where Ridgeway died had miraculously kept.

The Lucie Blackman case, which became one of the worst serial sex crime cases in Japanese history, also greatly affected the Metropolitan Police Department’s attitude toward sex crimes. Sergeant Mitsuko Yamaguchi, who appears in this film, was according to the director, the first woman detective to investigate a major sex crime in Japan and her compassionate attitude towards the victims shines through. She also does not hold back in declaring her anger and disgust for Obara.

When the detectives recall finally finding Lucie’s Blackman‘s body—dismembered and hidden in a cave, they discuss it with a rare mix of elation and sadness. They are glad that they can pin the crime on Obara but experience depression knowing that there is no chance she is alive.

Lucie Blackman.

Courtesy of Netflix

The ghost of Lucie Blackman

It turns out that for the detectives interviewed, the Lucie Blackman case colored their lives and the rest of their careers in a way that continues to rattle something embedded in their souls. Says Yamamoto: “All the detectives who worked on the case referred to her as ‘Lucie-san,’ [a sign of respect] which just does not usually happen on a case in Japan. They worked themselves to the bone to find her body.”

In the documentary, they can be seen remembering how they felt as they worked on the case. “I felt as though she were calling to us to come find her,” says Yamashiro, the rebel captain who defied the higher-ups in the agency and was instrumental in building a case against Obara.

No documentary is perfect and they do smooth over some disturbing details. Obara was never actually convicted of killing Lucie Blackman—-only dismembering her body. The film never addresses a important issues raised at the time: Several women raped by Obara had gone to the police with complaints, but were turned away or never taken seriously, because they were “workers from the night village”. Some would argue the disdain that the overwhelmingly male police force had for female victims of sexual assault allowed Obara to run amok for over a decade.

However, Ms. Tokie Maruyama, an assistant inspector at the time, also points out that one reason Obara eluded capture for so long is that he understood how to game the system. She told The Daily Beast, “At the time Obara committed his crimes, sexual assault was classified as a crime requiring a criminal complaint to prosecute. When a victim filed against Obara, his lawyer would find the woman and pay them lavishly to drop the charges—and the case would fall apart.”

The documentary isn’t just a police procedural. It also shows the compassion and emotional commitment detectives had for this case and their dedication to catching the criminal responsible. Years later, one of them went to England on his own to console Lucie’s mother Jane Blackman and pay his respects at Lucie’s grave.

Meanwhile, two of the detectives, now in their seventies and one clearly having some difficulty walking, every year make a pilgrimage to the cave where Lucie’s dismembered body was buried. They clean the debris and pray that her soul finds peace.

Yamashiro, who was given the Herculean and nearly impossible task of interrogating Obara and eliciting a confession, hopes the documentary will bring some closure to everyone involved. “Above all else, I hope that in some way that this film prevents another tragedy like this. It was horrific but at least this unrepentant criminal was taken off the streets before he could harm others and forced to face justice. That’s something.”