Last month, a House subcommittee chaired by Rep. Jim Jordan (R-OH) convened to investigate the alleged “weaponization of the federal government.” Witnesses, including two former F.B.I. special agents, testified to their belief that the U.S. Department of Justice and its Federal Bureau of Investigation have been targeting political opponents of the Biden administration. No bombshells dropped, but Jordan promises more to come.

If you doubt him, suspend your disbelief for a moment and suppose that Jordan’s subcommittee does produce convincing evidence of “weaponization.” Imagine further that F.B.I. agents, acting under direct orders from a vengeful Attorney General Merrick Garland, fan out across Jordan’s home state of Ohio, looking into the congressman’s past. Finally, envision that Justice Department prosecutors then indict Jordan on trumped-up charges, threatening to put the congressman behind bars.

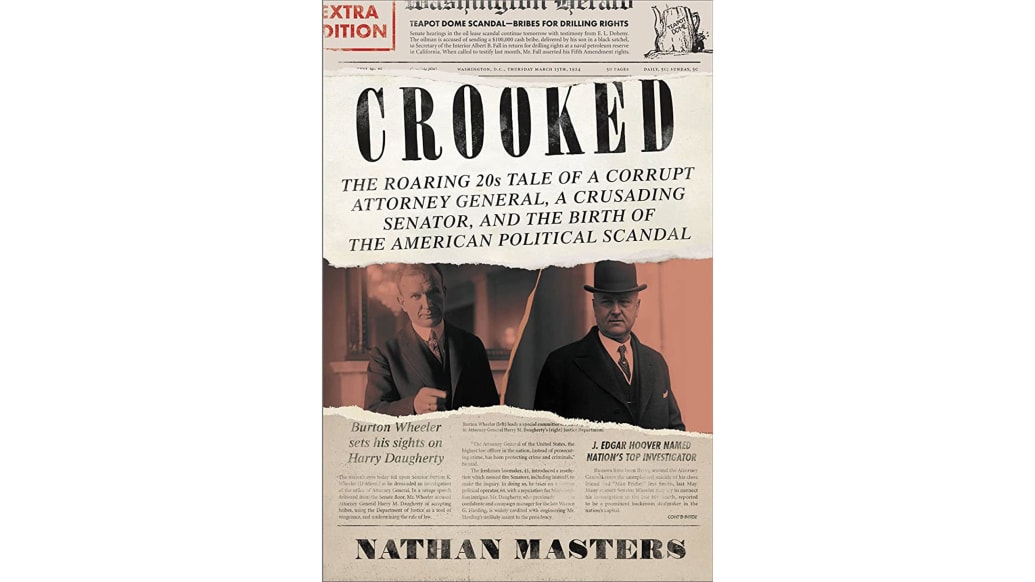

Far-fetched? In 2023, almost certainly. But as I recount in my new book, Crooked: The Roaring ’20s Tale of a Corrupt Attorney General, a Crusading Senator, and the Birth of the American Political Scandal, a similar scenario played out nearly one hundred years ago.

At the center of the storm was a firebrand senator and former U.S. attorney from Montana, Burton K. Wheeler, a Democrat, who was convinced that Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty, a Republican, was abusing his role as the nation’s top law enforcement officer. In March 1924, Wheeler took charge of a select committee especially set up to investigate the attorney general.

As a parade of colorful witnesses, including detectives, boxing promoters, and convicted felons, testified, Daugherty was perhaps the most unscrupulous person ever to head the Department of Justice. To cite just the most egregious example, Daugherty allegedly accepted $250,000 in protection money from America’s so-called bootleg king, George Remus.

More to the point, Wheeler’s investigation established that Daugherty had “weaponized” his department’s Bureau of Investigation, the forerunner to the FBI, to protect his friends, persecute his enemies, and settle political scores.

Founded in 1908 by executive fiat of President Theodore Roosevelt and his attorney general, Charles Joseph Bonaparte (grandnephew of Napoleon I), the Bureau of Investigation initially elicited howls of protest from Capitol Hill. Some raised the specter of the Okhrana, the tsar’s notorious secret police force. Others more pointedly invoked “Foucheism”—a reference to Napoleon’s ruthlessly effective police chief, Joseph Fouché, who, one critic recalled, “grew so powerful that he intimidated the emperor himself by reasons of the state secrets he held.” To these critics, nothing less than the independence of Congress was at stake. What would stop these government sleuths, they asked, from gathering kompromat on congressmen who refused to do the president’s bidding? Or from framing senators who pried too indelicately into executive branch affairs? They warned that the Bureau would inevitably devolve into a tool of political surveillance and repression. Government by blackmail seemed assured.

Under Daugherty’s handpicked director and friend of forty years, William J. Burns, a legendary detective with a well-earned reputation for dirty tricks, the Bureau seemingly proved these early detractors right. It refused to even open a case file on the brewing Teapot Dome scandal, and it harassed anyone who dared to peek under the rug of the Harding administration—even its own special agents. One was fired when his investigation into an interstate fight-film distribution scheme (in violation of federal law) led to some of the attorney general’s closest friends. Another was dismissed when his inquiry into Prohibition violations along the U.S.-Mexican border implicated a U.S. marshal who happened to be Daugherty’s brother-in-law.

Harry M. Daugherty

Library of Congress

The most damning testimony against Daugherty came from Gaston Bullock Means, a notorious sleuth who spied for Germany during World War I, bragged that he’d been accused of “every crime in the catalogue,” and nevertheless found an undercover job working for Burns at the Bureau of Investigation. Means confirmed what the Harding administration’s congressional critics already suspected—that the Bureau had been carrying out black-bag jobs to silence them. When one senator introduced a resolution to investigate Teapot Dome, for instance, Means ransacked his Capitol Hill office in search of compromising information. When another shared sharp words about Daugherty on the floor of the Senate, Means assembled a spy ring that infiltrated the senator’s inner circle and confirmed rumors that he’d fathered a child with his secretary.

“How it was going to be used, I don’t know,” Means said of the intelligence he gathered, “except this way, I would interpret it. If you found something damaging on a man you would quietly get word to him through some of his friends, or otherwise, that he had better put the soft pedal on the situation.”

And so, when Sen. Wheeler started hearing from his own friends that Bureau agents were snooping around his home state of Montana, combing over his past, he knew he was in the crosshairs himself.

On March 28, mounting evidence of malfeasance forced Daugherty’s resignation. Eleven days later, in an apparent act of retaliation, federal prosecutors indicted Wheeler on trumped-up charges of accepting legal fees from an oil company while serving as a U.S. senator, in violation of a longstanding statute. Although a dramatic trial eventually cleared the senator of all charges, such a nakedly vindictive prosecution undermined the rule of law and shattered Americans’ confidence in the federal government’s law enforcement bureaucracy.

“Jordan’s subcommittee cannot pretend that these institutions are still mired in the corruption of the Roaring Twenties.”

Almost a century later, as history’s echoes grow louder, we should remember that the potential for abuse within the D.O.J. and F.B.I.—even if long dormant—remains real. Blind trust in these institutions, especially as they sail into uncharted waters by investigating a former president who is also the presumptive frontrunner for his party’s next presidential nomination, would be an abdication of Congress’s constitutional responsibility.

Yet Jordan’s subcommittee cannot pretend that these institutions are still mired in the corruption of the Roaring Twenties. With its sensational revelations, Wheeler’s investigation shocked the American people, for perhaps the first time in the republic’s history, into caring whether the Department of Justice was living up to its name. Greater public scrutiny, in turn, encouraged professionalization among the ranks and inspired new institutional norms around political neutrality and prosecutorial independence. A half century later, those norms only hardened in the wake of the Watergate scandal and President Nixon’s demoralizing attempts to use the Justice Department as a political shield.

Today, prosecutors and investigators are expected to serve the rule of law, not a vindictive attorney general or the narrow interests of a political party. Moreover, the office once occupied by Harry Daugherty and John Mitchell (who went to prison for his role in Watergate) now belongs to Merrick Garland, a former appellate judge who, compared to his predecessors, approaches his job with near-judicial impartiality. To imply, as Jim Jordan has, that the Department of Justice is backsliding into its old Daughertian ways is not just irresponsible rhetoric that erodes confidence in our judicial system; it ignores a century of progress set in motion by Wheeler’s investigation.

Harry Daugherty died in 1941 a broken, discredited man. As Congress flexes its oversight power over the Department of Justice, it must confront realities of the institution today rather than exorcise the ghosts of the past.

Nathan Masters is the author of Crooked: The Roaring ’20s Tale of a Corrupt Attorney General, a Crusading Senator, and the Birth of the American Political Scandal. He has hosted and produced the Emmy Award-winning public television series Lost L.A. since 2016 and is the author of hundreds of articles about Los Angeles history. He works at the USC Libraries and lives in the mountains of Southern California with his wife, author and television writer Kseniya Melnik, and their two children.