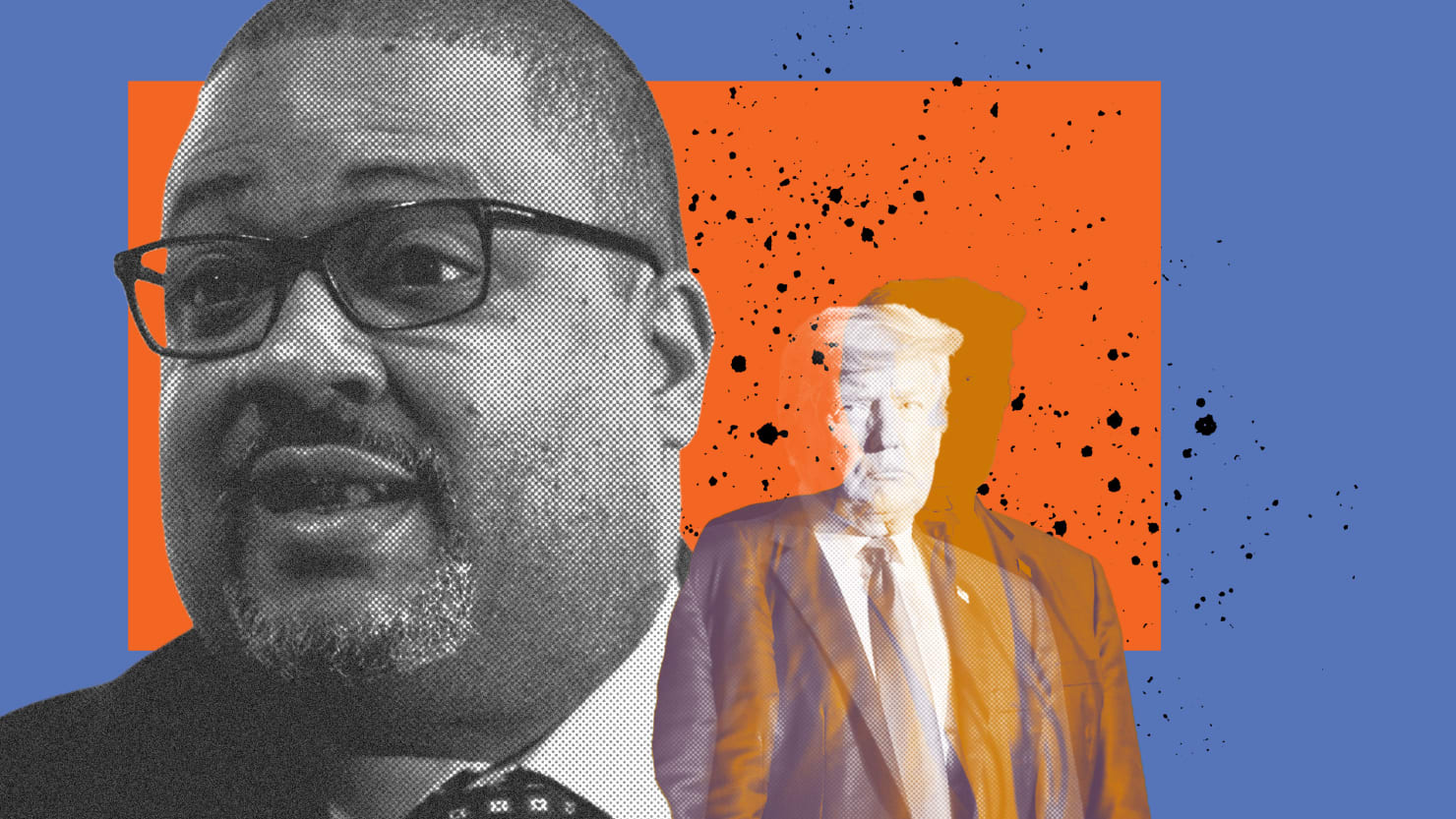

Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg’s invitation to former President Donald Trump to testify before a grand jury about the Stormy Daniels hush money case is an about-face from his previous reluctance to charge Trump for the financial crimes prosecution that his predecessor Cyrus Vance had appeared to green-light. But the sudden appearance of Bragg’s newfound prosecutorial libido may not bode well for the potential prosecution given the challenges it is likely to face.

As reported by The New York Times, Bragg’s invitation to Trump signals that an indictment may be imminent because potential defendants in New York have the right to answer questions before a grand jury prior to indictment. Reports that former Trump “enforcer” Michael Cohen also will testify before the grand jury further signals that Bragg’s investigation is very active. But if Bragg is really so far along in the prosecution, then the speed of the process is cause for concern.

Keep in mind that the potential financial crimes case against Trump that Bragg derailed had been worked up by his predecessor Vance for years. Vance began that investigation in 2018 and as part of it he fought Trump’s efforts to block a subpoena of his tax records held by his accounting firm Mazars all the way to the Supreme Court—not once but twice.

When Bragg tanked the case against Trump, the prosecutor who argued before the Supreme Court and won, Carey Dunne, resigned and another lead prosecutor on the case, Mark Pomerantz, who later wrote a book about his dissatisfaction with how Bragg handled the case, also resigned in protest. Bragg appeared unfazed by this extremely unusual situation and went on to blandly secure an arguably toothless conviction against only the Trump Organization. He also gave Trump Chief Financial Officer Alan Weisselberg a generous plea deal, for which Bragg got no cooperation against Trump in return for Weisselberg’s light sentence.

In sharp contrast to the exhaustive work done on the potential financial crimes case against Trump, the Stormy Daniels hush money case languished for some seven years before being revived by Bragg. That inaction was not Bragg’s fault. As set forth in a book by former U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York Geoffrey Berman, the Trump DOJ repeatedly interfered with the probe into potential federal campaign violations that could have arisen from the money paid to Daniels. Trump’s DOJ also told Vance’s office to back off any state charges. Seven years of inactivity damages any case—witnesses’ memories may have dimmed and evidence may have been lost—but the Daniels case also poses other challenges.

For starters, the main prosecution witness,Michael Cohen, is a convicted felon who, like most cooperators, has baggage that the defense can exploit. Cohen pleaded guilty and served time for lying on Trump’s behalf, so he will be subject to cross-examination about his credibility. The prosecution will need to prepare carefully to fight off defense attacks. The amount of that preparation grows in ratio to how much a witness has already said about the case. Cohen, of course, has made innumerable public statements about the case both sworn and unsworn.

Another challenge is that the legal theory Bragg must pursue in order to win a felony conviction is novel. The DA will have to prove that the falsification of Trump’s business records was meant to cover up another crime, such as a New York state election law violation. If Bragg can only prove the falsification, then Trump can only be convicted of a misdemeanor.

Then there are the likely legal challenges that Trump’s legal team could bring, including arguments that federal law on campaign finance violations preempts any state charges and arguments that Trump’s status as a former president means the case has to be tried in federal court. While those arguments may or may not succeed—and in my view they will not—they are also complex novel issues of law that will have to be fought through by Bragg’s prosecutors.

None of these are insurmountable challenges. Novel legal arguments are not necessarily hard for a jury to understand. Cooperators with baggage are used by prosecutors to secure convictions on a daily basis in cases, and the Manhattan district attorney’s office is more than capable of fending off Trump’s legal attacks. Most importantly, unlike the sprawling facts of the Jan 6 investigation, the Stormy Daniels case is a simple story to tell involving relatively few witnesses.

The worrisome issue is the seeming haste with which Bragg has gone from zero to 60 in his interest in prosecuting Trump. To resuscitate such a cold case like this one takes a very determined and bold prosecutor—adjectives not previously applicable in Bragg’s behavior toward Trump—so one is left wondering just how much Bragg is reacting to public criticism of him or even feeling a sense of competition with Fanni Willis, the district attorney for Fulton County, Georgia, who has been working her potential case against Trump for nearly two years.

Don’t get me wrong—I think prosecutors are to be applauded when they are unafraid to bring hard cases and try them. But haste makes waste is an adage equally applicable to criminal cases, and I hope it will not end up being the epitaph to any charge brought against Trump by Alvin Bragg.