As housing costs mount in cities across the country, an increasingly popular idea is converting urban golf courses into new homes. On paper, it seems like a great plan.

Golf courses often take up a tremendous amount of prime real estate for a sport only few people play. Meanwhile, developers and policy makers alike are keen to site new housing on land that doesn’t involve the expensive and often politically fraught prospect of tearing down existing homes or businesses.

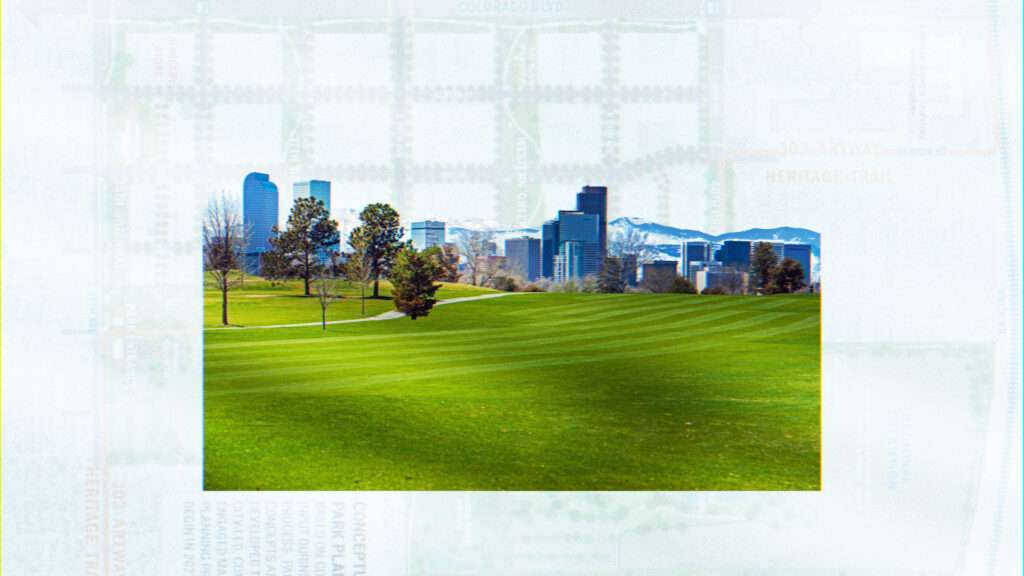

But the idea of repurposing putting greens for people is easier said than done, as evidenced by a bitter, years-long battle over the redevelopment of a private golf course in Denver, Colorado.

In Denver’s Park Hill neighborhood, sits a shuttered 155-acre private 18-hole golf course that hasn’t had a game played on it since 2018. The owner of the site, real estate company Westside, would like to turn the disused course into a mixed-use, mixed-income neighborhood featuring thousands of new homes, businesses, and a public park.

Doing so, they say, will help ease Denver’s ease mounting housing affordability pressures while also gifting the city what would be Denver’s fourth largest park. One 2022 report found that the Denver metro area had produced 69,000 fewer units than it needed.

“We have an actual plan with clarity around what we’re going to do and commitments in terms of community benefits and a financing mechanism to do that,” says Kenneth Ho, a principal at Westside.

It’s a plan that’s won the support of local YIMBY activists, affordable housing developers like Habitat for Humanity, and a majority of the Denver City Council.

“It’s an abandoned golf course right now,” says Tobin Stone, an activist with the housing advocacy YIMBY Denver. “The working class cannot afford to live in Denver right now. The best thing we can do is approve every big development that comes before us.”

But not everyone is so keen on big development.

Opposing Westside’s project is a motley crew of neighborhood activists, former Democratic lawmakers, and Denver’s one socialist city councilmember. All are fighting tooth and nail to stop new housing from popping up on the site. Instead, they’re demanding that all the golf course land, instead of a mere majority of it, remain as open space.

“The environmental impact of developing on green space instead of walking across the street and developing those hundreds of acres made no sense whatsoever,” Harry Doby, who resides near the Park Hill site and is an activist with the group Save Open Spaces (SOS) Denver.

Come April, city voters will decide in a referendum whether the Park Hill golf course will be redeveloped into homes and businesses, or if it remains a disused golf course.

Supporters and opponents are both hoping it will be the last word in a fight over the golf course’s future that’s been raging since 2019.

It was that year that Westside purchased the property. The plan had always been to transform the site into a mixed-use development in a rapidly growing area of Denver. Over the course of the next three years, it worked closely with the city government to hash out a detailed development plan for the site.

Their vision is to turn 55 acres of the 155-acre public golf course into 3,200 units of housing plus commercial and retail space. At least a quarter of the new homes, per Westside’s development agreement with the city, will have to be income-restricted units offered at below-market rates.

Westside is also agreeing to donate 80 acres of the site to the city, and dedicate the remaining acreage to parks and open space.*

The one major roadblock to Westside’s plans is a 25-year-old conservation easement. In 1997, Denver paid the former owner of the site, Clayton Trust, $2 million to agree to keep the land as a golf course.

Putting new housing on the Park Hill site requires the easement to be lifted.

Westside’s efforts to eliminate it have kicked up a storm of controversy from neighbors who’ve made a panoply of arguments against building on the old golf course.

Doby argues that developing the Park Hill site will be a huge loss for the environment. “In a climate crisis, in a heat island with a deficit of trees, you don’t cut them down and build on top of it. Not when you have alternatives that are equal and better,” he says, saying development would be more appropriate on nearby industrial properties.

These arguments have resonated with current and former elected officials and the city’s major daily newspaper.

Denver City Councilwoman Candi CdeBaca, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, has also criticized Westside’s development in various venues for its alleged environmental harms and for spurring gentrification.

The Denver Post has also come out against the project in a recent editorial in which it argued the city’s plan to lift the easement amounted to a “sweetheart deal” for Westside. The added development potential would massively increase the value of the company’s land far in excess of the community benefits they’ve agreed to provide, argues the Post.

It’s an argument that ignores the communitywide benefits of adding housing to the city. By the Post‘s logic, the city also massively underpaid the former Park Hill owner to accept the conservation easement given how much development potential it cost them.

Nearly a dozen former Democratic state legislators and former city elected officials have come out against the project as well.

Those former officials have joined as plaintiffs in two separate lawsuits filed by SOS Denver. Both suits argue that a court order is required to dissolve the Park Hill conservation easement, and that city actions preparing for development on the site are therefore illegal.

The first such lawsuit was quickly dismissed in early 2022, with a Denver District Court judge ruling that the plaintiffs lacked standing and a court order is not in fact required to lift the easement covering Park Hill.

SOS Denver’s second, very similar lawsuit, which is again joined by several former elected officials, was filed two weeks ago. The plaintiffs are being represented by Tierney Lawrence Stiles, LLC, a self-described “progressive” law firm that specializes in representing nonprofits.

While critics of the Park Hill development have so far failed in court and at city hall, they have had more luck at the ballot box.

In 2021, SOS Denver placed an initiative on the Denver ballot that would require the lifting of conservation easements to be put to a public vote. It passed with an overwhelming 64 percent of the vote. A Westside-backed ballot initiative that would have effectively exempted their property from this referendum requirement failed by a similarly wide margin.

In late January 2023, the Denver City Council considered whether to approve Westside’s Park Hill project and send the issue to voters. It became a heated clash of visions between supporters and critics of the development.

Opponents re-upped their arguments that the city would be losing irreplaceable open space by moving ahead with the development, all just to placate a wealthy developer.

“No one is talking about how potentially 10,000 new residents will impact traffic and quality of life,” said one opponent. Westside’s promise to keep half the site as open space “would be like living with half a lung,” said another.

“See if you see anyone tonight say ‘gosh I can’t wait for 12-story buildings across from my house’,” said one project opponent during the hearing. “I can’t wait for 12-story buildings to be honest,” Stone shot back during his time at the mic in a now-viral Twitter exchange.

Genuinely one of my proudest moments. https://t.co/BLuhZVKSn0 pic.twitter.com/8iEPiZR0FQ

— Tobin Stone (@tobinjstone) January 24, 2023

Other project supporters argued that building housing for people should be the city’s priority, not preserving open space. “I hear people talking about birds. I love birds. But they’re not more important than putting roofs over people’s heads,” said one woman in attendance.

These arguments proved convincing enough for most of the city council. The three holdouts included councilmembers Amanda Sandoval, Paul Kashmann, and CdeBaca, the latter raising a long list of objections at the January hearing. Westside would build units too fast and exceed the infrastructure needed to support it, she argued. She also said Westside would build units too slowly, meaning that rapidly rising incomes would erode the affordability gains from the project’s income-restricted units (whose rents and sale prices are based on the area’s median income).

“This is absolutely not a rezoning I would support even if the affordably is real,” CdeBaca concluded.

Those complaints notwithstanding, the city council voted 10–3 to put the Park Hill development before voters.

Doby, who is also treasurer of the “no” campaign, says he expects voting residents will see the Westside project for the raw deal that it is and shoot it down.

“It’s a bad deal for Denver because we’re giving away what we now know is more like 100 and something million dollars of development rights,” he says. “We get no compensation for that other than ‘oh great you can rent an apartment on what used to be a golf course.'”

Ho counters that if their development plan is rejected, the land will just go back to being a closed golf course that benefits no one.

“If we go back to a golf course, no one would be able to access it without paying a fee and walking around hitting a white ball toward a hole,” he says.

Correction: The previous version of this article misstated the nature of the open space called for in the development agreement between Westside and the city.