The Rattlesnake King was, by his own account, a man who wore many hats: cowboy, entrepreneur, and naturopathic healer, to name a few. Today, however, Clark Stanley is best remembered as one thing: being the original snake-oil salesman, a conman who tricked the public into purchasing his liniment for medicinal qualities it did not have.

During a demonstration at a 1893 world’s fair in Chicago, he reportedly slaughtered and boiled a snake, skimming its fat off and selling it as “Stanley’s Snake Oil” to a rabid audience. When federal investigators got their hands on the product to analyze, they came to the realization that Stanley’s Snake Oil did not contain any actual snake oil, but rather was made of mostly mineral oil. The Rattlesnake King was fined for falsely advertising his product, in violation of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. He paid a few hundred dollars in today’s money.

Social media is just the latest frontier of a fight that has played out between regulators and grifters ever since the Rattlesnake King’s time. Regulators have devised their fair share of enforcement tools: agencies like the Federal Trade Commission and Food and Drug Administration both have strict guidelines when it comes to promoting a health product. Under FDA guidelines, a drug must be “intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease,” and pass a lengthy approval process validating its safety and efficacy. The makers and sellers of dietary and nutritional supplements cannot make health claims about their products, which are not drugs. In the present day, Stanley wouldn’t be able to say that his snake-oil could cure snake bites unless the FDA approved snake-oil as a drug for this specific use.

But modern-day snake-oil salesmen have evolved, too. Savvy companies have replaced individuals like Stanley with armies of influencers to peddle supplements and make dubious health claims.

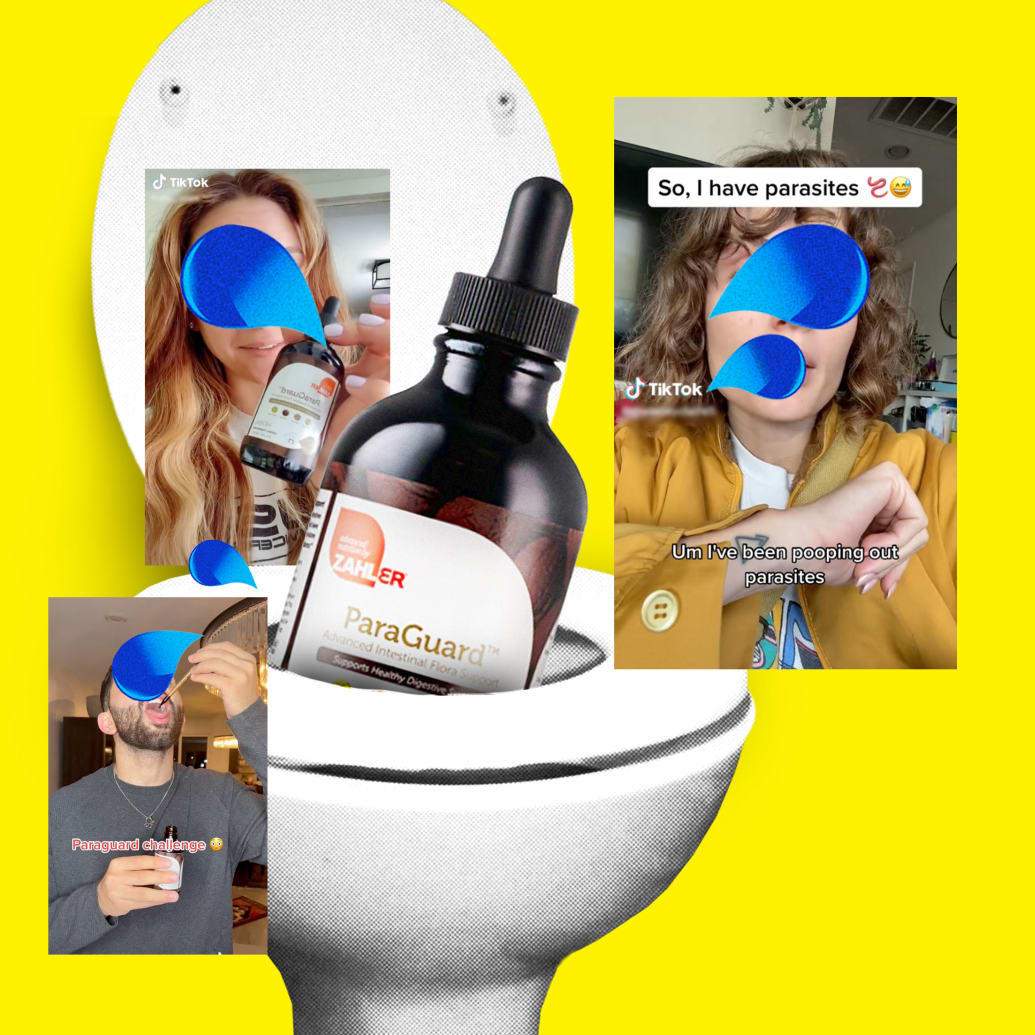

TikTok is a new battleground for this old conflict, where a supplement called ParaGuard, made by a low-profile company named Advanced Nutrition by Zahler, keeps going viral. The ParaGuard liquid, according to its packaging, provides “advanced intestinal flora support” through a blend of 10 herbs and essential oils: fennel seed, marshmallow root, black walnut hull, pumpkin seed, slippery elm bark, wormwood herb, clove bud, garlic bulb, oregano leaf oil, and peppermint leaf oil. ParaGuard’s product sheet claims that these herbs and oils “can be very helpful” at removing populations of “Bad Guys,” which are undefined but implied to be microscopic parasites.

The reach of the so-called “ParaGuard parasite cleanse” videos has been staggering. These posts regularly go viral, amassing millions of views from users who aren’t seeking out such content. TikToks tagged with the hashtag #paraguard have been viewed a whopping 146 million times in total.

At first glance, it appears that these videos are no different than any other in the popular “TikTok Made Me Buy It” genre. But the hashtags used are oddly uniform, including #paraguard, #zahlerparaguard, #parasitecleanse, and #zahlerpartner. Many creators also tag Zahler’s TikTok account in their videos. And many of these videos make near-identical unsupported claims—like insisting that 80 percent of all humans have intestinal parasites (which is demonstrably false.)

In short, it seems like these videos are ads.

Some of these videos include a grayed-out badge reading “Paid partnership” acknowledging as much, though many others lack this specific disclosure. If the brand is aware of influencers making unsubstantiated health claims about their product and failing to disclose paid partnerships—communications between Zahler and one influencer obtained by The Daily Beast suggest that the company is aware about several of these videos—legal experts interviewed say that the company could be at risk of violating the Federal Trade Commission Act.

“Modern-day snake-oil salesmen have evolved, too. Savvy companies have replaced individuals like Stanley with armies of influencers to peddle supplements and make dubious health claims.”

The Daily Beast contacted dozens of creators who posted videos about ParaGuard, asking questions to verify whether their content were paid advertisements. One influencer declined an interview, citing her busy schedule. Two responded to the request, asking the publication for paid collaborations. A fourth creator responded, confirming that her video (captioned with the word “ad” but not tagged with the paid partnership badge) was part of a paid partnership with Zahler. She did not respond to follow-up questions about the nature of the partnership, or any guidelines the company provided around content and disclosure. The rest did not respond to inquiries, and Zahler did not respond to repeated requests for comment about the health claims it makes about ParaGuard nor its advertising practices.

A spokesperson for the FTC told The Daily Beast that the agency does not comment on specific companies or products, and cannot not confirm or deny the existence of an ongoing investigation. But the FTC has sued a company and its owners before for using allegedly deceptive health claims and high-profile influencers to market and sell a viral product. Teami, and its paid influencers claimed that the company’s teas help consumers lose weight, “fight cancer, clear clogged arteries, decrease migraines, treat and prevent flus, and treat colds,” according to the FTC webpage on the case. Teami ultimately settled with the FTC in 2020, and the agency returned more than $930,000 to consumers who bought the teas.

ParaGuard is not an FDA-approved drug. As a supplement, it’s required to contain what’s on its ingredient sheet, but doesn’t need to undergo scientific testing to show it works. The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act prohibits the makers and sellers of supplements like ParaGuard from claiming they can treat, cure, mitigate, or prevent a disease like a parasitic worm infection. In fact, the FDA has previously warned a seller of ParaGuard for doing just that, heavily implying that some of the viral videos of paid influencers making similar claims would also be legally liable under the same guidelines.

A spokesperson from the FDA told The Daily Beast in an email, “Generally, the FDA does not discuss compliance matters, except with the company involved. The agency cannot comment specifically on this product, however, the FDA continues to be vigilant in its oversight to protect consumers from firms selling unapproved products and making false or misleading claims. Such products are illegal and may be harmful to consumer health.”

The controversy around ParaGuard isn’t a singular incident, confined to a niche social media community. Rather, it’s just one example of how the lack of oversight around social media has turned platforms like TikTok—rife with younger customers—into a modern-day exhibition stage for seemingly snake-oil salesmen selling products that may not do as they are advertised.

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Flickr Commons/TikTok

Potty Talk

Chris Satterwhite’s poop looked normal—and that was the problem. The podcast host had purchased ParaGuard liquid a month earlier and was following its “Intensive Support” protocol of 30 drops, four times daily. The supplement itself tasted horrible, like a cross between mint and bitter tree sap; he mixed the drops into bottles of water that he drank throughout the day. And after all that, he had nothing to show for it: no changes to his appearance or mood, and certainly no worms in his stool like he’d been promised.

Satterwhite will be the first to tell you that he doesn’t usually fall for scammy products, but he was convinced to buy a vial of the supplement after seeing videos for it on TikTok, seemingly made by average Joes.

“What I noticed was the ParaGuard product wasn’t mainly influencers posting videos, it was just regular, random people,” he told The Daily Beast. “If that was a corporate selling tactic, they did a magnificent job.”

“Now that I say this stuff out loud, I feel like I got bamboozled.”

— Chris Satterwhite

But when ParaGuard arrived in the mail, he noticed a flier advertising a promotion: Users could win free products by posting to social media if they tagged certain accounts and their videos received a certain number of likes. “Then I realized, well, that’s why they’re going crazy on social media,” he said. “Now that I say this stuff out loud, I feel like I got bamboozled.” Zahler did not respond to questions about the promotion, and by the time The Daily Beast spoke with Satterwhite, he’d long thrown out the product and the flier. But other, unrelated posts to TikTok appear to support the claim that promotional advertising was used to market ParaGuard.

While there are no scientific studies listed on major study databases that test ParaGuard’s supposed antiparasitic properties, medical experts are generally wary of these supplements’ ability to treat a parasitic worm infection, an infectious disease according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “These herbal medications are all pseudoscience,” Rojelio Mejia, a tropical medicine researcher at Baylor College of Medicine, told The Daily Beast. “There’s no FDA-approved herbal medication to get rid of parasites.”

(Zahler did not provide any literature showing scientific testing of their product.)

“These herbal medications are all pseudoscience. There’s no FDA-approved herbal medication to get rid of parasites.”

— Rojelio Mejia, Baylor College of Medicine

That doesn’t mean ParaGuard doesn’t work as advertised. But if it truly did, it would be in Zahler’s interest to seek FDA approval to sell the product as a drug. We have no evidence that eating a food like a cupcake can or cannot get rid of a person’s intestinal parasites, and there’s no need to conduct a scientific study showing that cupcakes don’t get rid of parasites, because they’re not drugs. But if a cupcake maker wanted to market and sell cupcakes as a treatment for parasites, the product would become a drug, and the cupcake’s efficacy would come into question.

It’s true that in some regions of the world like sub-Saharan Africa, parasitic worms infect a substantial percent of the population due to warm, moist climates coupled with poor sanitation. But in nonrural, upper-income parts of the United States with clean water and good sanitation, the risk of contracting an intestinal worm is very low, Mejia said.

Taking a dietary supplement to “deworm yourself” likely poses an even greater danger to one’s health than the specter of a worm. Herbal supplements like ParaGuard act as laxatives, causing a person who ingests them to pass stool frequently and have diarrhea, Mejia said. It may not be worms that ParaGuard users are reporting seeing in the toilet—it may be their own intestinal lining.

“That’s not a worm,” Mejia said. “That is your skin, your inside tissue, getting sloughed off, and it looks like a worm.”

And in serious cases (though none stemming from the use of ParaGuard as far as The Daily Beast can tell), chronic use of other herbal supplements and laxatives has led to documented liver toxicity as well as stomach ulcers due to the constant shedding of a person’s intestinal lining, Mejia said.

Catalina Goanta, a lawyer who researches technology law at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, told The Daily Beast that the nonspecific symptoms that creators point to in their videos—like fatigue, bloating, stomach aches, and acne—likely contribute to the parasite cleanse’s virality. Viewers may think, “Oh my God, I’m also bloated, maybe I have worms, too.” she said.

According to the CDC, most parasitic worm infections are asymptomatic, but depending on the worm, severe infections may cause a range of symptoms including anemia, diarrhea, and rectal prolapse. Doctors can diagnose parasitic infections by looking for eggs in a person’s stool or by testing their blood for specific markers that the immune system releases when it recognizes a parasite.

“It may not be worms that ParaGuard users are reporting seeing in the toilet—it may be their own intestinal lining.”

Mejia thinks there’s something about parasitic worms, also called helminths, that give people a knee-jerk reaction—and make them more likely to get tricked into buying a product that purports to rid them of worms they don’t have.

“All a virus like COVID looks like is one line on a card test. It’s a ghost to people because they have no idea what it looks like,” he said. “Bacteria is the same thing—you can only see it when it forms a colony. But parasites invoke something, because you have this wiggly, wiggly worm that can grow in humans, and they’re visible.”

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Flickr Commons/TikTok

Tricks of the Trade

“Brands are absolutely ridiculous, and they’ll find any way to take advantage of you,” Jada Jones, a 20-year-old content creator and actor from Charlotte, North Carolina, told The Daily Beast. She earns money by partnering with companies to promote their products on social media to her followers. At this point, she is so used to exploitative contract offers that she counters them with her own nine-page contract to avoid getting swindled.

But working with Zahler was different—“such a chill process,” Jones said. She reached out to the company in January via Instagram after seeing other influencers in the chronic illness space post about how ParaGuard improved their gut health. For the past nine months, Jones has been healing from topical steroid withdrawal, a rare condition that can occur after discontinuing long-term use of a steroid cream. Her skin condition limits the kinds of brand deals she can engage in, but after looking through the ingredients of ParaGuard, she determined the product wouldn’t exacerbate her flare-ups.

The next day, a Zahler representative emailed Jones to set up a partnership. Jones agreed to make four TikTok videos about ParaGuard, according to emails and a contract she allowed The Daily Beast to review. “i’m de-🪱ing myself 😳” reads the text on the screen of her first video.

When Jones worked with other lifestyle, fashion, and beauty brands in the past, companies would send her detailed brand decks containing specific language she was and wasn’t supposed to say. This time, however, she wasn’t required to run her videos by Zahler before posting.

“I genuinely think that they just put all faith in the content creator,” she said.

That blind faith could end up being a legal liability for both the company and its content creator partners, said Alexandra Roberts, a lawyer who researches media law at Northeastern University. A lack of oversight can introduce the risk of creators engaging in deceptive marketing, which includes making claims that a supplement can affect the structure or function of the human body. Put simply, if a product isn’t an FDA-approved drug, you can’t claim in paid promotion or advertisements that it has the effects of a drug—such as treating a parasitic infection, whether real or imagined.

“What’s really interesting here is that influencers are making drug-like claims about this product—and what it looks like is an unapproved drug under the FTC Act,” Roberts told The Daily Beast. “If it’s a drug that’s being distributed in interstate commerce when it’s not approved, that’s going to violate federal law.”

“What’s really interesting here is that influencers are making drug-like claims about this product—and what it looks like is an unapproved drug under the FTC Act.”

— Alexandra Roberts, Northeastern University

(As noted, neither Zahler nor any of the content creators contacted by The Daily Beast responded to questions about advertising practices or whether they believe they may have violated FTC rules.)

ParaGuard has been in troubled legal water before. In 2017, the FDA sent a warning letter to DoctorVicks.com, a Kosher vitamin supplier, alleging that the company was illegally advertising products including ParaGuard. In particular, according to the letter, DoctorVicks.com claimed on the shop section of its Facebook page that ParaGuard “fights worms and bug parasites” and can “rid the body of worms and other parasites”—claims that the FDA said violated the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act because they are not generally recognized as safe and effective for those uses. These claims, the letter continues, “provide further evidence that [the] products are intended for use as drugs” to treat disease.

A close-out letter that the FDA sent DoctorVicks.com in early 2018 confirms that the seller addressed the violations mentioned in the warning letter, including claims made about ParaGuard. Today, DoctorVicks.com stocks many products made by Zahler, but not ParaGuard. (Representatives from DoctorVicks.com did not respond to a request for comment on the warning letter or the subsequent changes made to address the violations.)

“If another seller is now marketing the same product with the same kinds of claims, it’s likely violating the law in the same kinds of ways.”

— Patricia Zettler, Ohio State University

Now, TikTok creators, some of whom are being paid to promote ParaGuard, are making awfully similar claims to those cited in the FDA’s warning letter. And when Zahler reposts creators’ videos on its TikTok page that claim ParaGuard can fight or rid the body of worms and parasites, experts say the company is wading into dangerous territory.

“If another seller is now marketing the same product with the same kinds of claims, it’s likely violating the law in the same kinds of ways,” Patricia Zettler, a lawyer who researches food and drug law and policy at Ohio State University, told The Daily Beast.

Asked to review the contract and email Jones was sent by Zahler, Roberts said that a few details caught her attention. First, according to the email, Jones was sent six “examples of past TikToks where this product has gone viral,” including links to videos that contained health claims and were not explicitly disclosed as paid partnerships.

The FTC requires influencers to make clear when they’re being paid to promote a product on social media, but Roberts suggested that a prospective partner who is sent these example videos might think that Zahler is condoning or even encouraging noncompliance in order to make posts to seem “organic and honest,” she said—in spite of the all-caps language in Zahler’s contract that states otherwise. Such a move “seems to imply that’s the kind of video [Zahler would] like this new influencer to make,” Roberts added.

It surprised Roberts to see Zahler’s laissez-faire approach to monitoring paid influencer marketing, since both the influencers and the company can be held liable for claims that violate the FTC Act by engaging in deceptive advertising.

When told about Roberts’ analysis, Jones said she felt like Zahler used a loophole by sending her example videos that contained health claims about ParaGuard’s ability to fight parasites and not telling her to avoid making similar claims. “They’re kind of saying, ‘This is what we want you to do,’ but not blatantly saying it,” she added.

In the absence of stricter enforcement, TikTok might seem like a Wild West for advertisers. Some of this perception is due to the app’s meteoric growth, and bountiful monetization opportunities: A report published last year by Insider Intelligence analysts predicted that influencer marketing spending on TikTok will outpace that on both YouTube and Facebook by 2024 to become the second-most popular social media site for advertisers. And according to one digital ad agency’s CEO, the mantra on the platform is to make TikToks, not ads—a sign of the lengths advertisers will go to make their paid posts seem organic.

“Companies have shifted from working with professional influencers who maintain massive platforms and keep lawyers on hand, to courting huge numbers of “nano-influencers” who may not be as well-versed in the relevant legal codes”

This approach has coincided with another trend: Goanta, the technology law researcher, said that companies have shifted from working with professional influencers who maintain massive platforms and keep lawyers on hand, to courting huge numbers of “nano-influencers” who may not be as well-versed in the relevant legal codes.

“How would the FTC even have even an overview of them all?” she asked. “This begs the question, do we need new approaches to do this type of digital monitoring?” One solution, Goanta suggested, might be introducing an option to report deceptive marketing in a paid partnership video on TikTok. The platform could take down videos that violate this policy and alert regulatory agencies of their existence for repeat offenders.

Photo Illustrations by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Flickr Commons/TikTok

In spite of all the doubt surrounding whether ParaGuard works and whether Zahler is promoting its product honestly, the company has its fans. Reached a couple of weeks after she began taking ParaGuard, Jones said that she’s noticed a difference from using the product. “I felt lighter and just better,” she said, and her bowel movements have been faster. Jones, who professed she doesn’t have much faith in the traditional medical system after her experience with prescribed steroids, said her paid partnership with Zahler has been positive so far. “I didn’t sign a contract that put me into a bad situation. I’m doing everything that I said that I would on my end, and the supplement still works for me.”

Such a testimonial can—and has—persuaded TikTok users to go out and buy ParaGuard. But consumers should not equate anecdotal experience with data, Mejia said.

“There are parasites in the U.S. But looking at the videos that are associated with ParaGuard, it’s clear none of those people” have the risk factors for a parasitic infection, he said. “There are risks involved with ParaGuard that go beyond having intestinal parasites. The ‘cure’ can cause harm.”