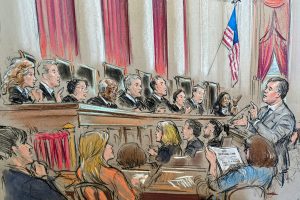

As the Supreme Court prepares to hear two cases that could decide the future of the internet, the regular partisan divide doesn’t seem to apply.

Look no further than the 27 attorneys general — Republicans and Democrats from states large and small, including California, Texas, Rhode Island and Alaska — who together are urging the court to restrict the reach Section 230, or what some have called “the twenty-six words that created the internet.”

Advertisement

The ‘90s-era law protects websites from liability based on their users’ posts. For example, while an individual author can be sued for a libelous blog post, the platform on which the text appears can’t be.

Notably, lower courts have interpreted the law’s protections to also cover recommendation algorithms. In Gonzalez v. Google, which the Supreme Court will hear Tuesday, the petitioners — family members of an American who died in the 2015 Paris terror attacks — are challenging this reading, arguing that YouTube’s recommendation algorithm helped recruitment for the self-declared Islamic State and therefore shouldn’t be shielded from lawsuits. Twitter v. Taamneh, a similar case scheduled for arguments Wednesday, also concerns tech companies’ liability for terrorism.

The 27 attorneys general seek to limit Section 230′s protections. Social media sites, they wrote in an amicus brief, don’t just provide platforms for content; they “exploit” it to make money using sophisticated algorithms. When Americans are harmed by criminal content pushed by those algorithms, they should have the right to sue the platforms in state courts, the attorneys general argued.

That’s where the bipartisan agreement ends. For every supporter of restrictions on Section 230 — and for every proponent of an expansive interpretation on the other side of the debate — there seems to be a unique motivation.

Advertisement

In New York, for example, the office of Attorney General Letitia James (D) has said that websites should lose Section 230 protections if they don’t take steps to prevent users from encouraging or planning acts of violence.

In Texas and Florida, after Republicans passed bills outlawing political discrimination by social media giants, they quickly faced tech industry lawsuits that cited Section 230 (and the First Amendment).

A similar suit was filed in California after the state passed a bipartisan bill setting rules for websites “likely to be accessed by children.” Attorney General Rob Bonta (D), in a press statement on the Section 230 brief, noted investigations he’d led into social media companies’ treatment of minors.

‘Killing People’

In other amicus briefs for the Gonzalez case, scholars and activists on both sides argue for a striking variety of causes.

The Anti-Defamation League said Section 230 should not automatically shield platforms from liability if they amplify hate and extremism. A brief from the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative referenced the case of a massive impersonation scheme by a man’s ex-boyfriend on Grindr, in which the victim’s lawsuit against the dating app was stymied by Section 230. The National Center on Sexual Exploitation and other groups pointed out that the law has been used to protect websites from suits related to their hosting of child sexual abuse imagery.

Advertisement

Notably, both President Joe Biden and his predecessor Donald Trump have expressed opposition to Section 230 — but for wildly different reasons.

During his 2020 campaign, Biden stated his opposition to the law after a New York Times writer asked about an ad that appeared on Facebook accusing him of Ukraine-related corruption. And in 2021, he raged that social media platforms were “killing people” with COVID-19 misinformation — a remark followed by a spokesperson’s announcement that the White House was “reviewing” Section 230. In a Gonzalez brief, the Biden administration argued that Section 230 does not protect against lawsuits based on the design and implementation of “targeted-recommendation algorithms.”

Trump, for his part, started ranting about the law after Twitter started fact-checking his lies about mail-in voting.

To be clear, Section 230 doesn’t exactly apply to Trump’s gripes. For now at least, the First Amendment protects sites’ ability to fact-check, censor or ban whomever they’d like, regardless of Section 230.

But some conservatives, echoing their leader, have said that supposed bias in content moderation ought to spell the end of the law’s protections. For the Gonzalez case, a group of Republican lawmakers led by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) argued that Section 230′s immunity for “good faith” content moderation does not extend to “removing or restricting content because of the politics of the user,” nor to “removing content that any eggshell-psyche user might possibly deem offensive.”

Advertisement

‘Free Expression Would Be Gravely Harmed’

Of course, Section 230 has plenty of supporters among tech giants and trade associations, but Meta and Google are hardly the only voices in the law’s corner.

Consider Wikimedia, the nonprofit parent organization of Wikipedia, which told the high court that without Section 230’s current protections, lawsuits “would deplete Wikimedia Foundation’s annual global litigation budget.”

Reddit, in its own brief, noted that Section 230 had provided immunity to a volunteer moderator of the site’s r/Screenwriting community against a lawsuit from the disgruntled operator of a screenwriting competition, whom other users had accused of being a scammer. In its own brief, Yelp argued, “Without immunity, deceptive reviews would flourish and consumers would be harmed.”

“Without immunity, deceptive reviews would flourish and consumers would be harmed.”

– Yelp’s amicus brief in support of Google

Various civil liberties groups and think tanks, including the American Civil Liberties Union, Cato Institute and Reason Foundation, backed the law as currently interpreted. And in a joint brief led by the Electronic Frontier Foundation, various library groups and the nonprofit Internet Archive said Section 230 was an essential protection.

Advertisement

“Internet users’ free expression would be gravely harmed” if Section 230’s protections were stripped from web recommendations and other basic tools, the groups said, arguing that these were the digital equivalent of newspaper publishers’ choices on layouts, photographs and font sizes.

‘A Backbone Of Online Activity’

Other groups, including the Bipartisan Policy Center and the Progressive Policy Institute, urged the court to let Congress amend the law if it wishes, rather than dramatically altering the interpretation in a decision. And some legal scholars have called for the law to be changed to account for “reasonable” efforts by websites to prevent illegal conduct. Multiple members of Congress have already drafted their own reforms.

Section 230 has been changed before, by a piece of legislation known as FOSTA, or the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act. Trump signed FOSTA into law in 2018, eliminating Section 230 protections for sites that facilitate prostitution and sex trafficking. Some sex workers criticized the move for spelling the death of safe online platforms for their work.

In the Senate, FOSTA received only two “no” votes — from Sens. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) and Ron Wyden (D-Ore), who was one of two authors of the original Section 230 back when he was serving in the House with then-Rep. Chris Cox (R-Calif.).

Wyden and Cox have both expressed reservations about the impact of their legislation. “The original purpose of this law was to help clean up the Internet, not to facilitate people doing bad things on the Internet,” Cox told NPR in 2018. And Wyden, speaking to The New York Times a year later, recalled a comment he’d made to a conference of tech workers, referring to the “sword” of moderation and “shield” of liability protection. “[If] you don’t use the sword, there are going to be people coming for your shield,” he said.

Advertisement

Still, Wyden and Cox wrote their own brief for the Gonzalez case, coming out in support of Google and against a limited view of the law they authored. The explosion of the internet since Section 230’s passage was evidence in itself of the law’s usefulness, they wrote.

“The real-time transmission of user-generated content that Section 230 fosters has become a backbone of online activity, relied upon by innumerable Internet users and platforms alike,” the brief read. “Given the enormous volume of content created by Internet users today, Section 230’s protection is even more important now than when the statute was enacted.”