.

“I remember being in the hotel,” he said. “My grandparents told me my father had gotten in trouble, and they asked me if I still wanted to go to the game. I didn’t understand what was going on, and I told them I did. We went, and it was awkward. It was surreal. I remember like it was played yesterday. I remember being there. But I didn’t know what happened until about a year later, and he wasn’t there anymore. It is what it is.”

Wilson Sr.’s life soon spiraled further out of control. There were arrests for fighting with police, possession of drug paraphernalia, and purse snatching. In December 1990, cops picked up Wilson Sr. in a Long Beach, California, crack house and booked him on an unrelated burglary charge. After getting out of jail, Wilson Sr. continued to decline. In 1999, he was hit with a 22-year prison sentence for stealing more than $100,000 worth of jewelry and camera equipment from a home in Beverly Hills.

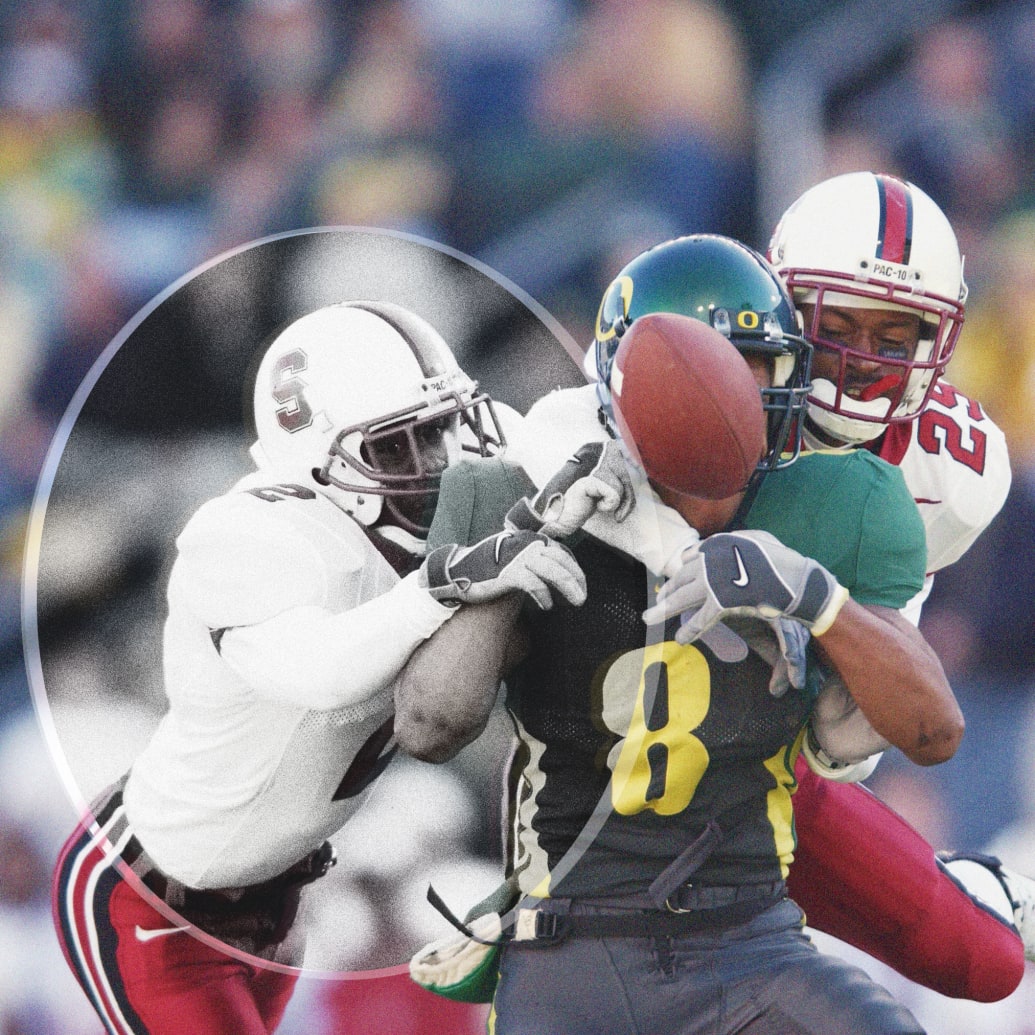

Running Back Stanley Wilson Sr. #32 of the Cincinnati Bengals runs with the ball against the Los Angeles Raiders at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on October 2, 1988 in Los Angeles, California.

Bernstein Associates/Getty Images

Prosecutors asked for a 25-years-to-life term under the state’s “three strikes law,” but the judge declined, citing Wilson Sr.’s mental health—his lawyer argued in court that his client suffered from bipolar disorder—as a mitigating factor.

Still, Wilson Sr. managed to remain a part of his son’s life while he was incarcerated. The two kept in close touch during the older man’s prison stint, according to Leigh Torrence, who said Wilson Jr., who started at Stanford in 2000, “was open about his struggles.”

“They were in contact, so he talked to his dad a lot and very much valued his dad and his opinion,” Torrence told The Daily Beast. “We kind of had, I guess, an admiration for all the things that Stan had overcome in his life. And the way he had done it was just so remarkable. You knew what he had gone through, but you would never have thought it. He didn’t show it.”

Christoff, Wilson Jr.’s former coach, also said his former player’s troubles didn’t appear to hamper him in any way. When he joined the team in 2001 after redshirting his first year, Wilson Sr. was just two years into what would ultimately be a 17-year prison term.

“We were aware of what had happened [with his father] and tried to be as supportive as we could, but I don’t think it was anything that ever affected Stanley from playing, or from a student standpoint,” Christoff said. “That I knew of, anyway. I mean, he would pick up all the coverage and plays very quickly. He was very bright.”

After four successful seasons at Stanford, the Detroit Lions picked Wilson in the third round of the 2005 NFL draft.

But his pro career was lackluster, lasting just two years. Wilson played 32 games, chalking up 63 solo tackles and deflecting eight passes. In October 2007, Wilson injured his knee and was forced to sit out the rest of the season.

Koren Robinson #81 of the Green Bay Packers tries to get around the tackle of Stanley Wilson Jr. #31 of the Detroit Lions at Ford Field November 22, 2007 in Detroit, Michigan. Green Bay won the game 37-26.

Gregory Shamus/Getty Images

The next spring, the Lions signed Wilson to a one-year deal. In August, he tore his Achilles tendon during an exhibition game, which ended his career.

That’s when Wilson went in a completely different direction, enrolling in the nursing program at New York City’s Hunter College.

“After football ended with Stan, he really threw his efforts into starting a new career in health care,” Torrence said, noting that Wilson had dreamt of becoming an anesthesiologist. “He had transitioned into that, which was something that just kind of fit him and who he was. It really just made a lot of sense that he would look to be helping others.”

Wilson graduated in May 2014, posting a smiling photograph of himself in cap and gown.

“The day finally came,” he wrote. “I graduated from nursing school. Thank you to all my family and friends that have supported me. Also thank you to those who unknowingly and inadvertently provided me with the motivation to keep going. #blessed to #finally #graduate. The true definition of #hereiSTAN #RN #nursing #huntercollege.”

Roughly two years later, Wilson’s path took yet another turn and began to mirror his father’s.

In June 2016, Wilson was shot in the abdomen by an elderly Portland homeowner who caught him trying to break into his house through a window, naked. When cops arrived, they found Wilson in a fountain in the backyard, and arrested him on charges of first-degree burglary and first-degree trespassing. Wilson had no prior criminal history, and his injuries were non-life-threatening.

In court, it emerged that Wilson was battling a drug problem, which reportedly included methamphetamine use. He pleaded no contest rather than copping a guilty plea because he “was not quite there” mentally at the time of the offense, according to prosecutors.

Hours before he was shot, Wilson that same day had broken into another home in Portland, where he fixed himself a drink and stole a book before the residents got back, according to police.

In January 2017, while charges were pending in the June 2016 case, cops again busted a naked Wilson outside another Portlander’s home. He had been “running around” in the homeowner’s yard, and seemed to be under the influence of drugs, authorities said at the time.

But roughly a week after being sentenced to three years’ probation for the initial break-in attempt, Wilson was back in handcuffs for another nude burglary attempt. He was charged with second-degree burglary, a Class C felony carrying up to five years in prison and a $125,000 fine.

Luckily for Wilson, the homeowner in that case agreed to a civil compromise: $10,000 in restitution and no jail time for Wilson, according to court records obtained by The Daily Beast.

But Wilson would soon find himself back in trouble. A little more than a year later, Wilson was arrested again—this time, for attempting to steal a car from a Portland Mercedes-Benz dealership.

From there, Wilson’s final descent was even swifter.

In August 2022, Wilson made headlines for yet another home invasion. This time, he twice let himself into a $30 million home in the Hollywood Hills, reportedly causing $5,000 worth of damage to the place. When officers arrived, they found Wilson taking a bath in an outdoor fountain, using soap he had pilfered from inside, according to reports. Wilson was charged with two felony counts of vandalism and one count of second-degree burglary.

Six months later, he would be dead.

After Wilson was booked into the L.A. County jail for the Hollywood Hills incident, a judge found him incompetent to stand trial.

This made sense to Torrence, who said Wilson’s arrests “seemed more a result of mental health than any criminality.”

It’s obvious that Wilson was often disoriented, either from untreated mental illness, drugs, or both. During one of his naked burglary and trespassing sprees in Portland, another homeowner encountered Wilson on her property in the hours before he was shot.

“He said, ‘Do you need anything?’” the woman told The Oregonian. “I said, ‘No, what are you doing in my garage?’ And then he said, ‘Isn’t this where I’m supposed to be?’ I said, ‘No.’”

At the same time, Torrence said there was no indication throughout their years together at Stanford, or later in the NFL, that Wilson was suffering psychologically. And there was no evidence of drug use while Wilson was at Stanford, either.

“The mental health stuff came some years after football,” Torrence said.

Although details remain scant, what is known about Wilson’s sudden death paints a stark picture of a life in freefall.

According to law enforcement sources cited by TMZ Sports, Wilson was being transferred Feb. 1 from the L.A. jail to the Metropolitan State Hospital, about 15 miles away. The state-run facility is organized into five sections, which includes a unit that serves the so-called PC 1370 population. “Within the larger framework of recovery and wellness,” Metropolitan State says of these defendants unable to be prosecuted due to mental illness, “an important treatment goal is the restoration of competency and return to court to stand trial.”

While Wilson was being admitted, he reportedly collapsed and died. Authorities said there was no foul play. However, John Carpenter, a Los Angeles-based attorney hired by Wilson Sr. and his current wife, said the family has its doubts about the official line.

“We are conducting a secondary autopsy, and so I’m holding back on commenting until we get confirmation on what our suspicions are,” Carpenter told The Daily Beast. “Early reports said ‘no suspicion of foul play.’ That is not the camp that we’re in.”

Carpenter, Torrence, and Christoff all said they didn’t have enough information to know if Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain condition that can occur after repeated blows to the head, was a factor in Wilson’s mental decline.

Wilson Jr.’s mother, through her husband, declined to comment.

Wilson Sr. was released from prison in 2016, spending more than a decade-and-a-half behind bars. He now lives in Wisconsin with his wife, whom he married shortly before going away, and their two children—one of whom majored in emergency management at North Dakota State University, where he also played running back.

Today, most major college athletic programs have put a spotlight on mental health.

“The health and wellbeing of our players has always been one of our top priorities at the University of Alabama,” Crimson Tide head coach Nick Saban said last year. “[O]ur goal is to positively affect the way mental health is viewed and treated in college athletics. Our hope is that every institution will join us in working to provide the best mental care for all student-athletes.”

In Wilson Jr.’s day, there was no mechanism in place that might have served as an early detection system, of sorts.

“Knowing his background, knowing the things that athletes deal with, the support you need is definitely something I think we’ve gotten better at,” Torrence told The Daily Beast. “I feel like the [era] just failed him, at not addressing some of the things [he might have needed]. For his life to have ended so abruptly was just heartbreaking.”

“We had him around all the time, so I guess we almost didn’t even realize how special he was to our college experience.”

For Christoff, Wilson’s death is a grim reminder of what could have been.

“It’s interesting—I didn’t get him, but I [also] recruited his dad,” he reminisced. “I had so many players that have just ended up in tragedy. There’s no reason for it.”