With 1.3 billion followers, the , published in March 2004.

Then-Vatican Secretary of State, Cardinal Angelo Sodano—the most powerful man next to John Paul in the pope’s long decline from neurological disease—pressured Ratzinger to abort the case. Six years passed. In November 2004, Sodano orchestrated a lavish celebration of Maciel’s 60th anniversary as a priest. John Paul, who would die five months later, praised the Legionary, despite numerous media accounts on the accusations. Sodano had once told The New York Times Magazine that the Roman Curia “is a brotherhood.” Ratzinger after a quarter-century in that fraternity of ecclesiastical careerists saw Maciel as a looming disaster for whomever the next pope might be.

“If the papal resignation and Vatican Bank reforms are Benedict’s major achievements, his struggle on the clergy abuse crisis failed as new scandals in Europe and America in 2010 saw a retreat into silence on that issue.”

When ABC reporter Brian Ross in 2002 approached Ratzinger outside his Vatican residence, asking about Maciel, the cardinal slapped his hand, saying, “No! Come to me when the moment is given,” and got into a waiting limousine.

So it was in late 2004 when Ratzinger, avoiding the ceremony for Maciel, ordered a canon lawyer in his office, Msgr. Charles Scicluna, to interview Maciel’s victims and compile a report. Neither man, cardinal nor canonist, knew that Ratzinger within a few months would be pope.

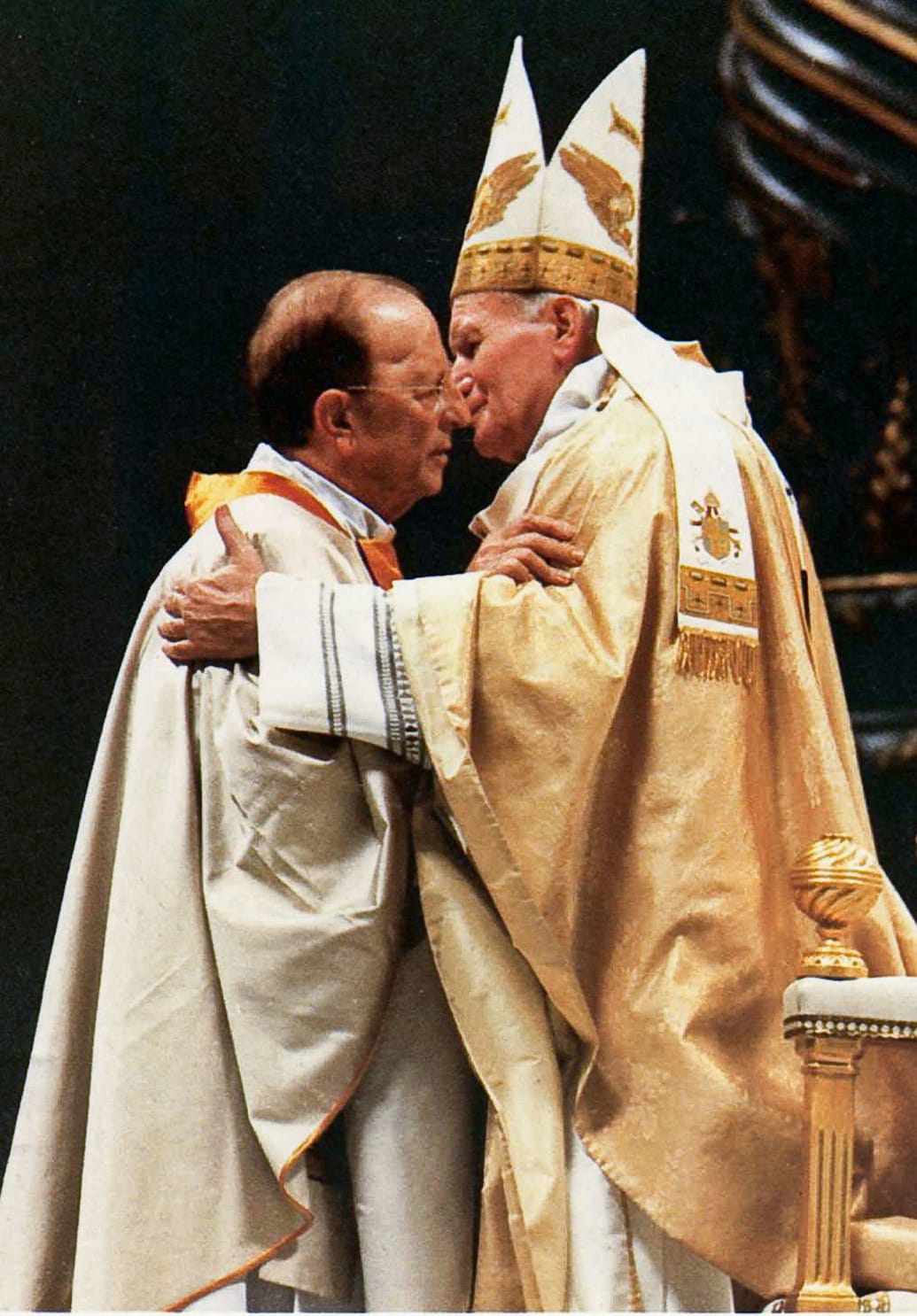

The Mexican priest Marcial Maciel is embraced by Pope John Paul II in a ceremony January 3, 1991 marking the 50th anniversary of the Legion of Christ order. Maciel, who died in 2008, has been accused as a serial pederast.

Maria Dipaola/MCT/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Benedict’s 2006 order, ousting Maciel from active ministry, shocked a host of conservative Catholics, not least John Paul’s biographer George Weigel, who sanitized his abysmal record in responding to clergy sex abuse, and Father Richard John Neuhaus, editor of First Things magazine who had declared “for a moral certainty” that the long-standing accusations against Maciel were “scurrilous” and false.

Maciel had long courted potentates like Carlos Slim of Mexico (who aided The New York Times with a $250 million loan during the 2009 financial crisis) and William Casey, President Ronald Reagan’s CIA director who endowed a building on the order’s Cheshire, Connecticut campus.

Maciel was the greatest fundraiser of the post-war church, and with at least 80 child abuse victims, the greatest church criminal of those years. Pope Benedict took a bold step in taking him out, yet the more fascinating story is why the pope did not go the extra mile to confront the pathological mindset left behind among Legionaries trained to report on anyone who criticized Maciel or their superiors—spying rewarded as an act of faith.

The Legion responded to Benedict’s expulsion of Maciel with a bizarre media strategy, claiming obedience to the pope, while stating that Maciel accepted the decision “with tranquility of conscience”—never acknowledging that their founder had abused anyone. Sodano, ending his reign as Secretary of State, insisted that the papal communique praise the Legionaries of Christ—who for nine years had counter-attacked the victims on their website.

Maciel left Rome for Cotija de la Paz, Mexico, and a reunion with his 23-year-old daughter, Normita, and her mother, Norma Hilda Baños. Maciel had seduced Norma in Acapulco years earlier, long supporting mother and daughter comfortably in Madrid, arranging for Normita to attend the Legion’s Northern Anahuac University in Mexico City. One of the great questions in the sordid life of Nuestro Padre is how many priests were sucked into the financial coverup as he supported Norma, Normita, and two sons by another woman who lived in Curenavaca. Their stories spilled in media coverage in Mexico City in 2010.

Joseph Ratzinger in the Academy of Sciences, moral and politic in Paris, France on November 08, 1992.

Raphael GAILLARDE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Norma and Normita joined the priests keeping vigil at the Jacksonville condo when Maciel died in 2008. The Legion announced that he had gone to heaven.

Benedict had the power to send word to the Legionaries of Christ: stop this lying, stop this charade, come clean about the demented Maciel, make amends to the victims. Why did he, as pope, tolerate such profane hypocrisy?

Benedict’s approach reflected his ecclesiastical culture. He appointed an overseer, Cardinal Velasio de Paolis, a Spanish canon lawyer who rewrote the Legion constitution and, in 2011, presided at a Mass in Rome, gloriously ordaining 49 Legionaries to the priesthood, men who had come up through Maciel’s system. De Paolis took Sodano’s “Curia is a brotherhood” ethos in advancing new men to clerical life.

Why, with all the evidence that Benedict had, didn’t he order an intervention strategy of therapy for men saturated—brainwashed—by Maciel’s coercive tactics? Why didn’t the Vatican take a careful long view, assessing how mentally healthy each Legionary was to become a priest?We’ll likely never know, but Benedict accepted a circle-the-wagons strategy to preserve Maciel’s movement.

The Legion coverup of Maciel’s progeny continued for a year after his death, a time in which the Legion kept affirming its obedience to Benedict, without any admission that Nuestro Padre had abused anyone—a strategy that called into question the pope’s very dismissal of Maciel.

Vatican officials had learned as early as 2005 that Maciel had a daughter, as Cardinal Franc Rodé, who oversaw the Congregation governing religious orders told me in a 2012 interview in his Vatican apartment. Rodé, a huge admirer of Maciel and the Legion’s militant orthodoxy, admitted (as I had been told) that he had seen photographs of Maciel with his daughter by a priest in the know. Rodé said he shared the information with the investigator, Scicluna, who undoubtedly shared it with Cardinal Ratzinger who commissioned his probe.

Why did Cardinal Rodé refuse to take disciplinary action against Maciel? “I was not his confessor,” he said.

“Why, with all the evidence that Benedict had, didn’t he order an intervention strategy of therapy for men saturated—brainwashed—by Maciel’s coercive tactics? ”

In following the Maciel saga after the 2007 death of my good colleague, Jerry Renner, I found new sources as men kept leaving the Legion. In 2010, three such priests revealed how Maciel used the Legion’s wealth to further his ends. He guided cash payments to cardinals like Sodano, often $5,000 at a time for coming to say Mass, or the $50,000 given by one Mexican donor for the privilege of attending a private Mass in the chapel of Pope John Paul II, “an elegant way of giving a bribe,” as one ex-Legion priest called the thick envelope handed to the pope’s Polish gatekeeper, Msgr. Stanislaw Dziwisz (today a cardinal back in Poland, his cover-ups of child abusers have been extensively covered by the TV journalist and author Marcin Gutowski).

Pope Benedict XVI gives Christmas Night Mass at St. Peter’s Basilica on December 24, 2009 in Vatican City, Vatican. The mass on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day are scheduled to be televised in an estimated 73 countries.

Franco Origlia/Getty Images

Maciel bought the silence of Vatican officials to preserve his status after years of child molestations.

Though he would not sanction an intervention of the Legionaries, Benedict did order Legion superiors to negotiate settlements with abused ex-Legionaries—to my knowledge, a breakthrough position for a pope in a church which by then had paid out billions in U.S. court cases. Yet Benedict backed away from mounting evidence of the cult tactics that shaped the Legionaries’ behavior, letting the late Cardinal DePaolis “reform” the religious order.

The Legionaries by 2019 had entered something of a reform mode, announcing that since 1941, 175 minors had been abused by 33 of the order’s priests. Maciel had abused about one-third of those priests, the statement said.

By then the Legion was lurching from abuse lawsuits. In 2021 the Pandora Papers Report by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) found that the religious order held two trusts worth nearly $300 million in assets “at a time when victims of sexual abuse by its priests were seeking financial compensation from the order through lawsuits and through a commission overseen by the Vatican.” The legion told ICIJ that “religious institutes do not have an obligation to send detailed information to the Vatican regarding their internal financial decisions or organization.”

Had Benedict XVI taken the hard decision to dissolve the order, take its assets into receivership, and provide therapy and new assignments to men seeking religious lives, he would have set a standard for future popes to follow.

Instead, Francis inherited the ongoing scandal of the Legion of Christ.

How does one account for a pope’s failure to arrest a criminal sexual underground in the priesthood that has done monumental damage to the church?

Benedict’s theology, shaped by the ideal of obedience to the pope as a higher moral realm, faced a more urgent pathological reality of church governance. Canon law is an administrative code that does have penal measures which few popes, cardinals or bishops over many years showed interest in using. “The sad duty of politics is to establish justice in a sinful world,” the American Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr famously said.

That ideal, premised on free speech as a cornerstone of human rights, held scant legitimacy in Cardinal Ratzinger’s theological prism. Morality turns on obedience. The cardinal who denounced “a dictatorship of relativism” as pope had no justice system capable of arresting the crisis symptomized by Maciel. Flawed as we know democracy to be, the rule of law—genuine law—as the Trump debacles have shown, is a standard from which civilization cannot retreat. Canon law, warped by bishops and cardinals concealing sex crimes, is a case study of moral relativism, writ large—defending “the good of the church.”

The cardinal—who for nearly three decades meted out justice against religious thinkers and activists according to a moral barometer dictated by papal power—discovered, as pope, that he had no true standard of justice when he needed it most. Abiding by the “brotherhood” of the Curia, he refused to oust several Irish bishops who played musical chairs with pedophiles. Maciel as a religious order superior stood outside the Curia, his crimes of a greater magnitude. Yet In the end, the ecclesiastical culture that empowered Ratzinger to enforce moral truth as a dictator would, imposing silence and excommunications, could not meet the challenge he faced as Benedict of the church’s worst crisis since the Protestant Reformation.

A longtime contributor to The Daily Beast, Jason Berry has written extensively on the Catholic Church, including “Render Unto Rome: The Secret Life of Money in the Catholic Church,” which received the 2011 Investigative Reporters and Editors Best Book Award.